This author, illustrator, game designer and lover of mice agreed to chat with me about living a creative life.

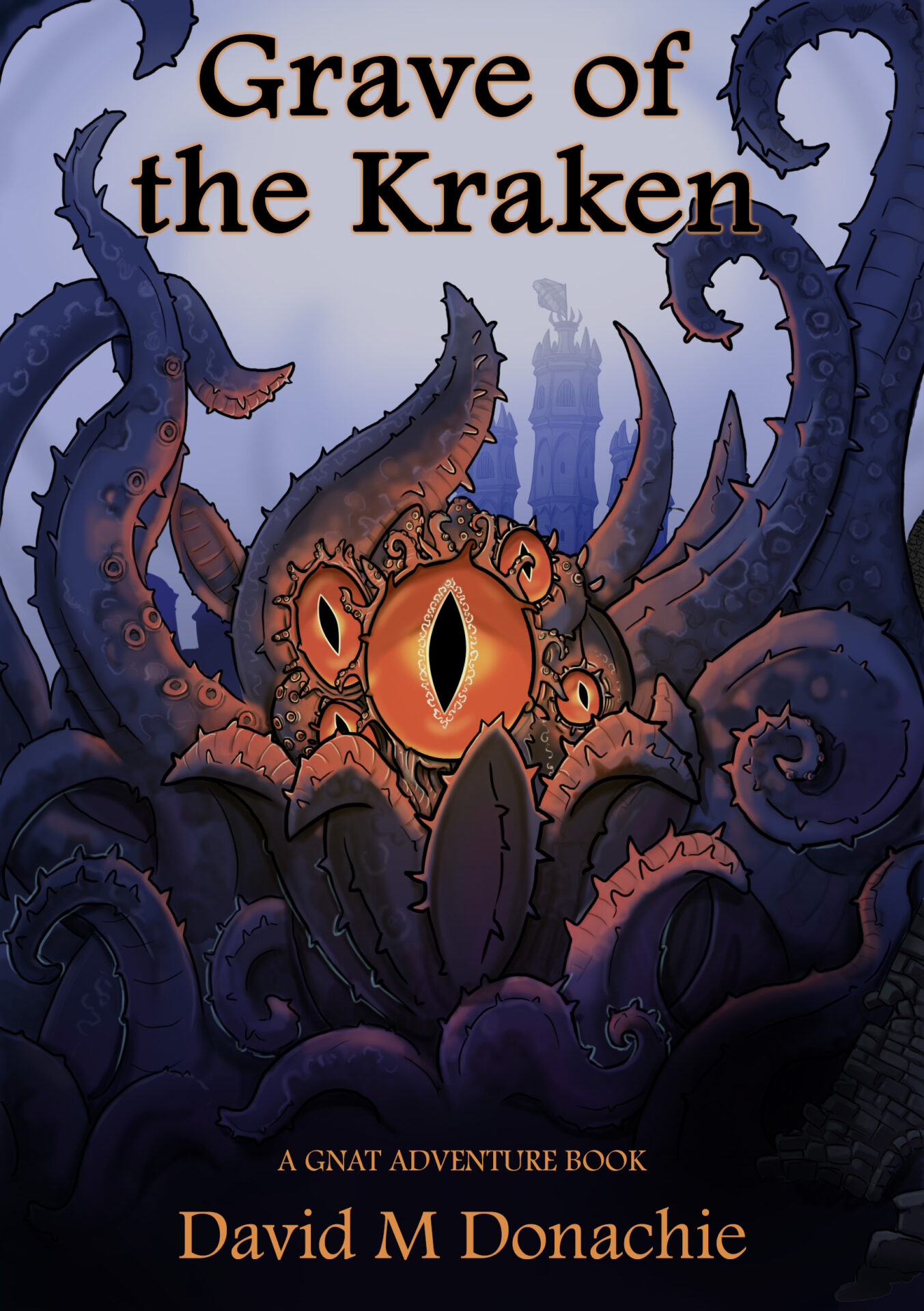

Here are just a few of the things he’s had a hand in: a series of free Dragon Warriors modules with Red Ruin Publishing, a TTRPG where you pilot a spaceship made of dice, and the versatile GNAT System for gamebook adventures—which he used to write Heart of Keros, a free, excellent adventure and Merit Award winner from the 2023/2024 Lindenbaum Competition (which is where I first found his work).

J: My first question is, how did you start writing?

D: I’ve been writing a really long time. I found not very long ago some short stories I’ve written when I was, I dunno…ten, maybe? Which I Sellotaped together in books, because I was really keen on having a book with my name on it, but I only had Sellotape. I don’t think I even had a stapler, so (laughs) the whole spine is Sellotape.

But I stopped for quite a while. I was writing right through into my late tens, my early twenties, and then…I dunno, I just kinda stopped doing it for ages. I had some attempts at writing novels and they hadn’t really gone anywhere. Either I hadn’t finished them or I’d finish them but didn’t like them, or in one case, I finished it but nobody else liked it. (laughs) So it kinda put me off.

I moved into game design more than just straight-up fiction because I found that easier. A sort of mixture of game background and rules was easier. And then about ten years ago, I had an idea for a novel really just floatin’ around in my head, because I hadn’t done anything with it.

Ya ever watch Time Team? It’s an archaeology program, and they had a special about Doggerland, which is the area of land that used to be in between the UK and mainland Europe, where the North Sea is now. I had this idea about writing a novel that was set there just before it was destroyed by a tidal wave, and I’d forgotten about it, and ten years later I saw a repeat of that episode, and I thought, “I’ve gotta write this!” And so I wrote a manuscript for that, and then I looked at it and thought, “(sigh) God, I’m really rusty and out of practice. I need to redraft this, but what I’ll do is I’ll write some shorter fiction to properly up my writing craft, and then I can go back to that manuscript.”

I found that this time I really liked writing short fiction, and so I started to write a lot of very short flash fictions, and I got into some writing groups and spent a little while submitting things to writing contests before I realized they were almost all scams. And I realized you didn’t have to enter contests, you can just send things directly to anthologies and they will like your stuff, and pay you for it, rather than the other way around!

After a while of doing that, I thought, “Actually, I’ve got enough things that were okay. I can put this in an anthology, and then maybe I’d actually have a book in my name.” So I did that, I self-published that. And then I went back to the novel and thought, “Okay, I can do this a bit better now.” And then that was picked up by a small publisher over here. It’s a while ago now. Four years ago, maybe? Something like that.

It came off the back of “I have to write this novel,” and a bit of “I’m not very good at it anymore, so let’s practice.” That’s probably how I’m back to writing now.

J: One of my questions is, “How do you practice?” And it sounds like maybe you learned by doing, by making short stories and releasing them into the world.

D: Yeah, absolutely. By the time I’d gone back to writing fiction, I had been writing for games publishers for a while, and that gave me contact with editors who actually know what they’re doing. The kind of editor who doesn’t just correct your spelling mistakes but actually tells you that your structure is wrong. One of those gave me some input on that novel in its kind-of-early stages, and that was very very useful. Just craft things like saying, “You’re writing an action scene, your sentences have to be short and punchy to suit the action,” that kind of thing.

But on top of that, just a lot of reading. I read a lot, so often, I can think of something I’ve read that’s got the right kind of structure for what I want to do. It’s not always directly applicable, but often. I probably go through…let’s say about a hundred books a year, on average, so yeah, a lot of reading. But it does take learning by doing to transfer that into actual writing ability, because people are always like, “Oh, if you read a lot, you’ll learn how to write.” No, if you read a lot, you’ll learn how you wanted to write, but it doesn’t mean you can do it. For me it was just, “Do it.”

I did do an English Literature degree, but they did not encourage creative writing, so.

J: I actually did a Creative Writing degree, and I’ve been around English classes, and…I don’t imagine there’s a lot of creative writing. And I don’t even know how much I learned from my degree, to be honest.

D: I mean, I learned something. I learned things about poetic meter, and different kinds of novel structures. I know how you can put an epistolary novel together, and that kind of thing. But that’s not practice. It’s all vague theory about how books work and how stories work, and I’m not sure it’s any more useful for the actual writing process than all the Save the Cat! stuff is—which is, again, teaching you theory on structure, but it doesn’t actually help you put sentences together that anyone would want to read.

So I think you just do it, and then you find out what people like. I set myself up a goal for this anthology. I wanted to write fifty-something stories, and then I could find good things in that. At least fifty percent of them were sort of rubbish. (laughs) And they were things I would write and I’d be really enthused about, do lots of research, I’d think “this is great,” and then you’d look at the finished story and you’d think, “This is kind of boring!” Or give it to someone else and they’d go, “Nah, I don’t like that one.” So nah, I won’t do that. Put that on the Rejected pile!

To me, practice is what actually works. Practice and feedback from people. Having a group of people who don’t just say “yes” or “no,” “I thought this was any good,” but will actually give you the more detailed feedback to say “this bit works” or “this bit doesn’t work, this is why it doesn’t work.”

I’m in an eight-person Discord-based writing group where we all look at each other’s stuff, and that’s been really useful, because you get a whole different kind of feedback from that then you from, I dunno, giving your story to your dad, who’ll tell you that it’s great. (laughs) Say, “Oh, well, thanks, Dad. It’s good for my self-esteem, but it doesn’t help my writing get better.”

J: What did it take for you to commit to writing again—and what led you back to it? (Editor’s note: I am painfully aware that he answered this question already.)

D: That’s what I was saying about wanting to do that novel. They say—this is something I’ve had loads of writers say to me since I picked it up again—you don’t normally get to write what you want, to be honest. You tend to write to a market. Or you write things that nobody reads. You’ve got a choice. You can write your passion stuff, you can write for a market, and maybe if you’re really lucky and you’re like a one-in-a-thousand person, what you wanted to write also creates a market.

Most of the time they say you don’t write your passion project. But in this case, that’s what drew me back. I wanted to tell this particular story, and so I was just like, “I have to write this. I don’t care if anyone reads it or not.” The fact that it then got published by someone was a real bonus, I was very happy about that, but in a sense, I just had to write it for me rather than anything else.

Marketing: Who Do We Write For?

J: Once you had it written and it was getting published, how did you feel about being in the business zone somewhat? Because I imagine that as soon as it starts making money, the thought comes in that now it is more business and marketing.

D: Yeah… To be honest, for that novel, it hasn’t made a lot of money, so that’s fine. For gaming projects, it’s always been like that. You do a thing out of passion and you put it out there, but if people start paying you for it, you start not then doing what you want, you do what they want. And you’ve got to constantly promote it, because if you stop promoting it, people will forget about it, and I have always really hated that particular side of it: just the grind of making sure that you’re on the Facebook groups and that every time someone has a promotion for book advertising, you’re putting in for it, or every time the right genre is mentioned, you’re there, saying, “Oh, by the way, I wrote a book about that that you might be interested in…”

It’s thankless, and it…it’s soulless, because although there are people who’ll tell you they love your stuff, most of your interactions just result in people ignoring you, right? Somebody says, “I really wish there was a novel about this entirely specific subject,” and you say, “I’ve got one,” and they don’t respond. Or they say, “Nah, doesn’t look [like it’s] for me.”

It is a fact of book publishing now, book writing now, that publishers expect you to do that work. And I’ve been told by people I know who’ve been writing for longer that they didn’t used to be quite like that. There used to be a real industry behind the big publishers taking your work, and they did the promotion, right? To some extent, that’s still true if you’re, like, one of the biggest writers in the world, or one of the biggest publishers who will put work on bookshop shelves and who will advertise it for book prizes and so forth. But for most authors, we’re expected to do the work and your publisher is not doing that much to help you. They may give you suggestions and guidance, but you’re still expected to do the work. So if you just want to write and not publicize, it’s really hard, and I think the year of the writer who writes away in obscurity in their secluded country house while somebody else takes care of all the promotion is just gone. Even if you have an agent, they’re not promoting it for you, they’re promoting it with you.

So yeah, I don’t really fancy the business side of it. It’s always held me back in the game production side as well. It’s a similar market…except slightly less congested. There’s a little more chance of you getting something out there and not promoting it a lot, and nevertheless having people pick it up and like it. What I’ve found, oddly enough, is if you spend a week making a game and put it on sale somewhere for $3, it’s more likely to get randomly acknowledged than a work of fiction you spent months on and then put on Amazon, and I think that’s just because there’s so much stuff on Amazon. The smaller the venue, the more likely you are for people just to pick your stuff up without your direct input all the time.

J: That makes me wonder…are gamebooks in an awkward space in between where technically they can be on an Amazon storefront, but…maybe you would rather have it on an RPG aggregate?

D: Yeah, absolutely. In fact, I think the majority of gamebooks appear on both Amazon and DriveThruRPG, for example, and they are seen in two different ways by the people who are buying them. People who are on DriveThru or are on Itch, maybe, they see them as gaming products primarily, and they put them in the same mental category, say, as journaling games or solo adventure games like Four Against Darkness. They are seeing it as a game product. But people who buy it on Amazon see it as a fiction product, and their requirements are quite different. So if you put it on Amazon and it doesn’t have illustrations, and it isn’t available on paper, and it doesn’t have traditional dice-rolling, people don’t like it. You put that on Itch and people will be much more sanguine about it, but on the other hand, they don’t like it if they don’t have a PDF with hyperlinks and that kind of thing.

It’s different markets. The people who are physical gamebook buyers are the people who grew up on Fighting Fantasy or Lone Wolf or something like that. They want that experience of holding a paper book in their hand and going from numbered section to numbered section and rolling dice, and there’s even a kind of art that they expect, there’s a kind of black-and-white line art that Fighting Fantasy books had that I think is sort of like a standard: everyone wants that in their gamebooks, even if it’s good to have some entirely different kind of art. Or no art. But it feels to people like it’s “not a real gamebook” if it doesn’t “ape” that kind of 1980s, 90s aesthetic that those books have.

I see that in a lot of Facebook groups where people are advertising their gamebooks. They are advertising it to people who already want gamebooks, and their gamebooks are on Amazon for people to get, and they are in paper, and they will always show a picture of it in a paper format like you would advertise a novel…and they’ll tell you that it uses some familiar dice system that you’ve seen before so you don’t need to think about it…whereas the same people who are putting things on Itch don’t publicize it that way, right? They don’t need to show you a paper product ’cause you’re getting a PDF, and that’s what you’re happy with. The price point is completely different.

So yeah, it does, it straddles things. I find even sometimes, designers aren’t always clear whether they’re calling it a solo adventure or a gamebook, and I think those two things mean different things to different audiences. It’s a solo adventure if your audience are tabletop RPG players who don’t have a group at the moment, and they’re unsure whether they’re going to play that or Lady Blackbird or…what’s the one I just picked up yesterday? Apawthecary—with “paw” in the middle because it’s bunnies making medicine.

But when you’re on the other side of it, the Amazon side of it, it’s a gamebook because if you said to those people “it’s a solo RPG adventure,” they wouldn’t be interested. They want a particular category of what they see as distinct fiction.

So it’s an odd, straddling-a-boundary kind of form.

J: I’ve been wondering about the art side and thinking that not only do I wanna improve my art skills (which, I know, a constant thing), but think about aping the Final…the Fighting Fantasy style. I didn’t even grow up with Fighting Fantasy. I grew up with Final Fantasy, and video games.

D: Yeah.

J: I just came to it later. As a kid, I had done things like draw mazes and games and books, and write comics and short stories, and eventually I learned gamebooks besides Choose Your Own Adventure existed, and dabbled in high school—and stuff like that. But in art, I was always inspired by things like Final Fantasy or anime. And I don’t think that would appeal to a lot of people.

D: I wonder, though, if there’s room for that, because there’s different traditions. I mean, if you look back at the Endless Quest books that TSR published, their art style was quite different. It was a bit more “tabletop RPG supplement” and less gritty. And they also did HeartQuest, which was their romance brand, and that has a very different art style, quite naturally. I have a big collection of paper gamebooks, and there are things like these Asterix ones, which just have Asterix illustrations; there’s Tintin ones; I’ve got an Enid Blyton Famous Five one; I’ve got ones which are historical novels, like Survive Your Way Through the French Revolution (although the art for that is a little bit more like the Fighting Fantasy ones, to be fair).

Fighting Fantasy style is also adapted for slightly low-resolution pulp printing, right? So some anime art wouldn’t work very well in that if you’re going for the more pastel-y shade version. It doesn’t necessarily print well, and if you’re getting Amazon to do your printing, like a lot of people end up doing, they can be quite inconsistent on grayscale. Sometimes it’s very poor, and it’s a bit of a luck-of-the-draw as to which printer printed a particular copy. Whereas black-and-white line art is more reliable. So you draw for the medium, at that point.

But I don’t think there’s no room for something else. Just because the sort of self-styled “grognards” who grew up with Fighting Fantasy when they were kids want a particular thing, you can’t only write for them, because they will—no disrespect to them, I’m in that category—will die! (laughs) Hopefully maybe before the gamebook genre does! Also, if you go for the PDF version rather than paper version, your art choices are so much more expanded, right? You can go with color, you can go with all kinds of different art…and you can sell that, if you’re selling more on the RPG side. If you’re selling it directly on Amazon, yeah, you may be more constrained, at least until people like your stuff enough that they’ll buy whatever you do. Then you can surprise them and go, “Yeah, I know everything up ’til now has looked like a Fighting Fantasy adventure, but this time, you’re getting anime.”

J: That’s kind of what I was imagining as a best-case scenario…and then some in multiple styles.

D: Yeah, well, there is always that. For instance…I did a whole bunch for the Dragon Warriors game, and I did those during COVID because, like most people, I was locked up indoors with nothing much to do. I played Dragon Warriors when I was in school, and I found a group on Discord who were fans, and they were like, “Oh, we all love this game, but there’s not been enough new material written in recent years for anyone to play,” and it’s like, “Well…everyone’s into solo gaming right now, so why don’t we write some solo stuff?” There were a couple of us who all enjoyed the idea, so we did them, and I’ve done some semicollaborations with them. Theoretically I’m doing a proper collaboration with one of them now, but he’s being really slow, for a collaboration! (laughs) So we’ll get there, but no time quickly.

And that is quite a distinct style, because Dragon Warriors is a role-playing game from the same period as Fighting Fantasy. So it’s got a lot of the same design aesthetics, got a lot of the same kind of atmospheric stuff. It fits into that traditional game style. But then we’ve gone off and done some other things—he’s done other things. He got a bit more into the fact that those books didn’t make any money because the fan license for that game doesn’t allow you to sell stuff: you can make it and give it away for free, or you can cover your cost of production in the case of physical copies, but you can’t profit from it. (laughs) So we both thought after a while, “Well, we’ve done like a dozen of these between us, and they’ve been downloaded a hundred thousand times, and it’s great, but…we haven’t actually made any money for any of that, and maybe it would be nice to write a game you could charge for!” (laughs)

So we’ve both gone off and written other things. And I think his style has changed a bit in the other things? I don’t know if my GNAT stuff is in a slightly different style. I think it is, a little. The setting is much more fantastic. Art-wise…yeah, the one I’ve done on paper, the art was much more atmospheric grayscale rather than the dense line art stuff. So I think maybe I felt the same way, that as soon as I changed system and changed setting, I could be more free with the art.

J: Do you feel that you’re striking a balance between what the market wants and what you want with some projects?

D: Yeah, I think for the gamebooks especially. I’ve also gotten into doing computer interactive fiction stuff, and that’s way more experimental. People writing interactive fictions that are just about their morning coffee, or enduring Chinese New Year dinner with your family. But when I’m writing gamebooks, I slot it into a more traditional mold. I want there to be places to explore and possibly a monster you hit with a sword or something, and I find it easier to write in that mode, and conveniently that’s what the people want out of a gamebook as well, for the most part! (laughs) If all the interactive fiction stuff had made me want to do much more experimental things on paper, I think I would struggle, because I think no one would want to read them.

My last interactive fiction game was about a mouse riding the mouse subway and not remembering why he was on the subway, and you have to work out which stop he was supposed to get off at…which is a place he was going to get his scarf knitted. That wouldn’t work in a paper gamebook! (laughs) No paper gamebook reader would want that story. So, yeah, you do. You write for the kind of reader, and it’s just convenient if I happen to enjoy writing that. So if you really hate the kind of stories that traditional gamebooks tell, then writing them will be agonizing, or writing ones that don’t work like that will be agonizing trying to get people to play them, is my suspicion. But if you do happen to like that style of adventure story as shown in those books, then people want to play that, so it’s not so bad.

Readers, Fans, and Motivation

J: I’m currently writing a story that I kind of wrote because I thought it [the style of art and writing] would be easier for me.

D: Yeah.

J: But now that I’m on the last book…it doesn’t feel like it’s challenging me in a way that I want.

D: Yeah, I get that. There was an author who was proofreading stuff for a couple years back, who had what I thought was a nice series of books about some ancient Picts who get cursed by the god of death so they can’t die. Each novel jumped forward a couple of centuries, talking about the same characters in different historical periods, and I really enjoyed that, but he got to about the third book and suddenly he just couldn’t stand these characters anymore, and he couldn’t stand the jumping of settings, and …you could see he was itching to write something different.

But obviously he’d sold people on this idea of a series. He was self-publishing them, but he had readers, who wanted to see those story arcs, who wanted to see those characters, and he really wanted to write something different. I know that was very difficult for him, which is probably why in the fourth book, they all get killed when Mount Etna erupts, I think. (laughs) He kind of found his way out. It’s like, “Ohhh no no no, I can’t deal with the ten books I thought I would write. I will kill everybody in Book 4 and try to make it seem satisfying.”

But yeah, it is very difficult, and I often wonder about the writers who make all their fortune with a particular character or particular series, especially mystery writers. You write a book about a detective and it catches on, and then you can’t write a book about any other detective. I can only imagine how much you must hate that character eventually. You saw that with Sherlock Holmes, where Conan Doyle just tries to kill him because he doesn’t wanna write Sherlock Holmes stories anymore. And then nobody wanted to read anything he wrote unless it was Sherlock Holmes. They had to bring him back from the dead.

I like the Ian Rankin Rebus novels, and he had started with a relatively old detective, so eventually he retired, and now he’s being forced to write all these books about him after he’s retired working on cold cases and stuff, just with more and more implausibility about how this man is still doing anything at all. Because really no one wants to read books that don’t have their favorite character in them.

Yeah, I understand the being trapped in a series you didn’t want to write, or you don’t want to write it anymore, even though you thought you did.

One good thing, though, about gamebooks, in that note, is…people are not hot on continuity. They don’t care that they start over with a different character in a different setting each time. In theory, I’ve always written my gamebooks so that you could take a character from one to another, but I don’t know how many people do that. My guess is, not that many. That does give you a nice excuse in just jumping setting. Dragon Warriors has one I did in a fairy-infested wood, and the next one was in a desert, and then the next one was in the arctic, and there’s one set in a jungle—it gives you this freedom to just jump around and say, “I don’t wanna write about those people, I don’t wanna write about that setting, now I want to do a completely different thing,” and you can get away with things as well. Say, “Oh, well, the next one’s a murder mystery.” Right? Yeah, people go with that! “Oh, a game with a murder mystery! Oh, that’s fine.” So I do think it’s quite a nice flexible sort of format.

J: Do you think you’re getting a bit of a following of people…like five people who are taking a character between books and thinking, “I can’t wait for this interconnected world to grow more,” and are thinking about it in those terms?

D: I really hope they are? Yeah, I’ve only had a couple of people tell me that they’ve done that. Which is very nice, I like that.

I make an assumption that most people won’t notice the clever things you do in your stories. In the short story collection The Night Alphabet I told you I did, all the different stories were not related, but character names were repeated, in slightly different assortments, so that the same names would come up from story to story. I thought no one at all had noticed it, and then someone was just saying, “I really loved the way character names repeated, and it made everything feel interconnected, and left me wondering how they were connected and what the secret connections were.” And that was great! I’m like, “One person noticed, but it was good.”

So yeah, I suspect there’s a really small number of people waiting for the next GNAT gamebook…but not necessarily telling you. I don’t think the gamebook reader crowd is as responsive as, say…novel or video game fans. They’re much more likely to tell you what they want to tell you, their theories about your book, and I suspect that’s because they identify with the characters more…as in they’re given a character that they have to inhabit mentally. But in a gamebook, it’s always just you. So in your head, the character is really just you. And in a weird way, that makes you identify less, because it’s not somebody else you want to learn more about. It’s just you, and you already know about yourself. It’s not as interesting. And that is helped by the way that gamebooks tend to be written in second-person, say “you are doing,” “you see.” So it’s not like “our character who you are interested in sees”—”you see.”

I think there’s this weird thing of…people like that, they love getting involved in the story, but they’re not going to be emailing you saying, “I must know the next adventure of this character,” because there is no character.

J: Well, isn’t there that one exception, Legendary Kingdoms—which I haven’t read, I’ve only heard of it—where you specifically have a group of characters and they have story arcs? Do you think people ask about those characters and think about them?

D: Maybe? I’d love to think they did. There was the same kind of thing in Blood Sword, where there are four distinct main characters with their own arcs, and you can move between them, and they get different kinds of story choices, and they’re definitely much more personified because when you’re playing one, you interact with the others, so you can see those characters on the page rather than just in your head.

But that’s not the default mode, so I suspect that although people have played around with that, it hasn’t revolutionized how people see gamebooks enough to make them want to do it. Unlike the taking a character from story to story, though; Fabled Lands made that very successful. There’s nine, ten, eleven Fabled Lands books, and you are assumed to be taking a character from one to another. They really took the idea of an open world in a gamebook to its biggest extent. And you could just, oh, get on a ship, and it would say, “Right, you sail, to paragraph 30, book 4.” Those books are not stories, they are places that you are exploring, which is maybe a different mode from quite a lot of gamebooks.

J: I was interested in you talking about interactive fiction, and wondering if that’s another venue that helps you be creative and experimental in a way that other media doesn’t.

D: I think it does…mostly because the practitioners are in a very different headspace, and that’s partly because of the way the market works, because people tend to directly publish on Itch, and they tend to make their games free, and that gives you a completely different mindset.

If you think of flash fiction as being maybe more experimental than longer-form fiction, you’d think that flash fiction was all about experimental form, but it’s not. Flash fiction is all about writing for flash fiction anthologies in an entirely rote manner, and people who do mainly flash fiction just churn it out in huge quantities because if you buy a lot of flash fiction anthologies, you see the same names in all of them.

That’s because there’s a ready, paying market for people who want to put out fiction anthologies, but they don’t want to have to pay much to contributors. If you tell people they’re only gonna give you $5 for their short story, they’ll go somewhere else, but if you tell them you’ll give them $5 for their fifty-word flash fiction, they’ll do it. Or $1, or exposure, or something. It’s an easy way to fill up a book.

But because the interactive fiction authors are mostly not writing for fee-paying markets, I think that immediately gives them more freedom. There’s been a big tradition of text adventures having a much higher proportion of ethnic minority writers, of LGBT writers, because they’re a form of game design that’s outside the commercial norm, and also because the tools are really accessible.

It’s hard to produce a standard video game. You need programming, you need art, you need playtesting and bug fixing, and all the rest of it. But a text adventure, you just need to be able to write text. You don’t need an artist, you don’t need anything else. Most of the packages for creating text adventures make that really easy. You just write text in boxes and make links between them… It makes it a really accessible, sort of underground creative space where people can tell nonmainstream kind of stories.

Yeah, that is something that really encourages experimentation. And it’s almost like the mirror image of gamebooks. The gamebook readers, they want traditional adventures with exactly 400 paragraphs, and a fight every five pages, whereas most of the interactive fiction people, if you produce that kind of game, they’re not interested in it. They want a game that’s exploring grief or sorrow or breakups or…exploring an abandoned museum that is actually an allegory for your own generational pain—whatever it is.

So yeah, I think it does encourage a completely different kind of creative activity. Even just the fact that they have a subcategory for kinetic poetry.

I always see poetry as being where mainstream publishing allows you to go and do something that isn’t just writing to market, right? If you’re producing a book of poetry, it’s sort of expected that you’re gonna be doing something personal and different. It’s a bit like literary fiction, which I always think of as that special category for “I wrote a book and it’s not marketable, but I’m a good writer and I’m famous.” “Uh, it goes in literary fiction, then!” People will pay premium prices for it with the understanding that they may not read it, and it will go on their shelves so they can look at it and go, “Oh, yeah! Yeah, I’ve heard about that book. Is it great?” “Ooh, yeah, House of Leaves is really great! I absolutely finished it!” (laughs) I…never finished House of Leaves. I think it’s very clever, but I couldn’t get to the end.

So interactive fiction is in many ways more like poetry, right? It is more experimental, it is more free, whereas the physical gamebook writing or gamebook-like writing is more towards the self-published short fiction anthology kind of realm. It’s not quite self-published novels, which are mostly fan novels or trying to be. It’s not quite in that space, there’s no big intellectual property that gamebooks tend to be trying to sell out to.

You certainly don’t see many gamebooks that are fan works for some other media, and I suspect that’s because they’re too much effort compared to writing a fan story. Writing a fan story is comparatively easy: you just indulge all your fantasies about how you wish you were in that show, and nobody cares if you don’t write very well. (I’m lookin’ at Twilight. (laughs)) But gamebooks have more mechanical work. There’s all that checking that your numbering is all right, and the item that you picked up on page 15 actually has a use, and you didn’t forget a keyword, and you can’t get stuck in a loop, and that kind of stuff. And that’s not amenable to the fan writing mindset, I suspect.

Making Gamebook Creation Less of a Hassle

J: It’s an interesting thing to think about. I never really compared fan works to gamebooks or even interactive fiction.

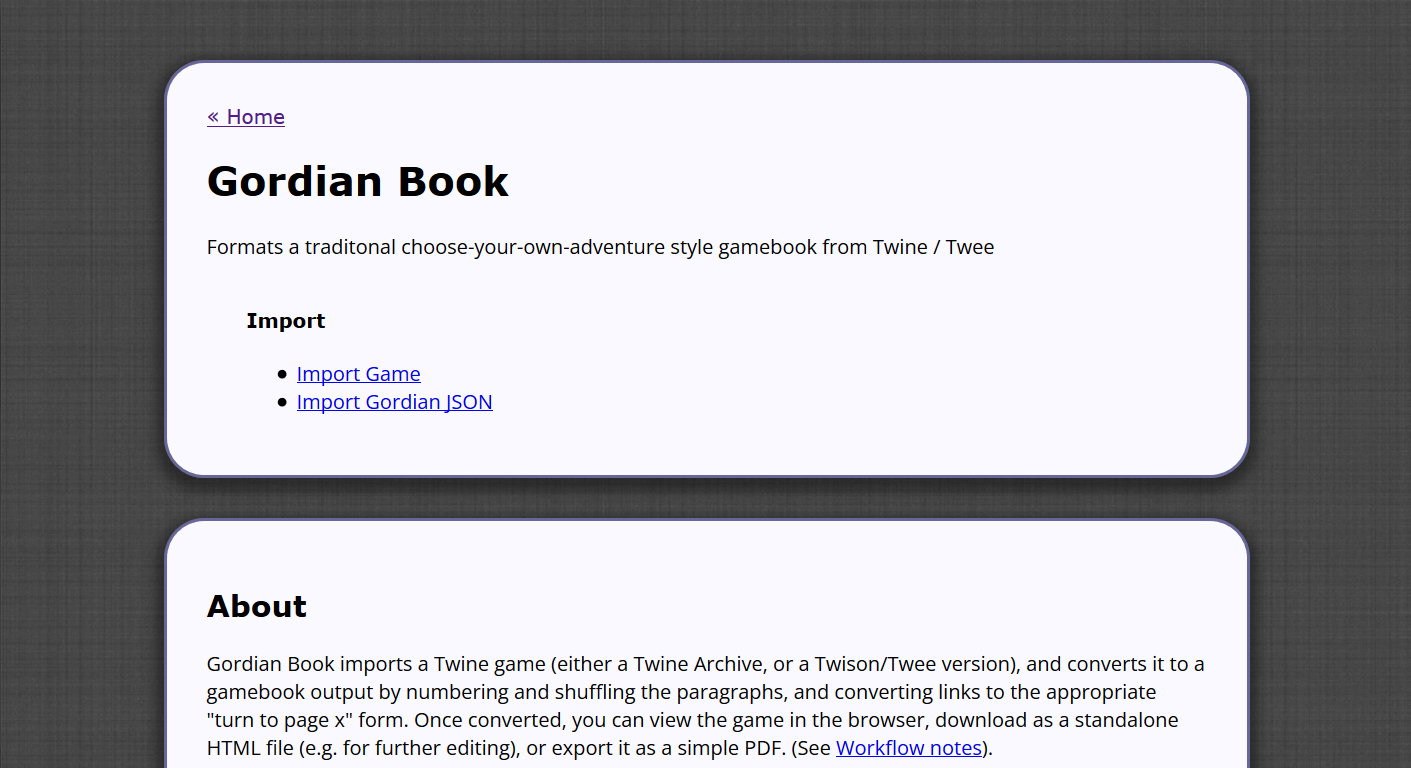

D: Yeah. Part of my thinking in the overlap there is that I use interactive fiction tools to write gamebooks, and I have ever since I came back to it. I have a bunch of gamebooks I wrote in my teens on paper… I wrote lots of numbered sections first, and then when I needed a section, I would look through it for something that looked like the right size, and just hoped that whatever I wanted to do would fit into it. When I came back to the idea of writing gamebooks, I was like, “There’s gotta be a better way. There’s gotta be good software for this now.” I looked and it turned out there was only a lot of very mediocre software. There were a few unmaintained Windows-only things, there were a few online but very clunky things, and there was one thing that was paid for and quite expensive, and I thought, “This, this doesn’t make any sense at all.”

So I went looking for just text adventure tools and I found Twine, and I thought, “Why can this not just be turned directly into a gamebook? Why has nobody done that?” Turns out a couple of people have over time, but they’ve not publicized it very well. I found out the wrong way around. I went, “There’s no tool to write paper gamebooks out of Twine; I’ll make one”—made one, made gamebooks with it, told people about it, and then found out about the other ways I could’ve done it! (laughs) Afterwards, from people going, “Oh, I remember seeing something like that a decade ago.” “Oh, well, I wish I’d known that in the first place. Maybe I wouldn’t have had to write my own.”

At least mine is more…accessible to people, because it’s just a website. You can just go there and use it, and I’m always encouraging people to do it. Whether anyone is interested in my systems or not, I’m just like, if you are writing a gamebook and you are sitting there numbering paragraphs in Word by hand…please don’t do that! Please just use this free software to do that bit for you. If you then wanna paste it all back in Word afterwards ’cause you like the way you format text in Word, that’s fine, but don’t try maintaining all the links and tracking all the keywords and stuff yourself on paper when there’s a tool to do it.

J: That would be on the Tools section of your site, right?

D: Yeah, so GordianBook.art has its own website. That’s just the Twine-to-PDF-adventure-book site, and I have gone directly from those PDFs to things I’ve published on Amazon. So it’s perfectly fine for doing that. The other person I’m collaborating with, for ages he was being resistant to that. He’d always just written things in Word and numbered sections by hand. I was like, “I’ve got this better tool,” and he was like, “Nooo no no, I like the way I work.” And then after a bit, he was like, “You’re doing these really quickly”—and I’m like, “Yeah, because I’m not doing what you’re doing!” (laughs) And he’s like, “Ah, I’ll try it.” Now that’s the only way he does things. He’s totally abandoned the way he did it before because this is much more convenient!

Every time I see people on Facebook and they’re always like, “Oh, what’s a good bit of software?” I’m always like, “Psst! Use this! use this free stuff! Don’t torture yourself!” If I do nothing else than just make writing more gamebooks easier for people, that will be good.

J: A service to the hobby.

D: Yeah! Exactly, exactly.

J: I like that.

D: Yeah, I like the features in it that have come when somebody’s approached me and said “can you have little pictures of dice at the bottom of the screen?” or “can you do this?” and I’m like, “I ‘unno, maybe.”

J: And now it can be done.

D: Yeah! Yeah, exactly. I dunno if I’ve ever put the option visible for the dice at the bottom of each page, but it’s there.

Selling In Person

J: Now I have some…business-slash-company-related questions. How do you feel about selling at in-person venues?

D: I feel that I shift far more copies in in-person venues. For all the gamebooks, I have had much more ease shifting them in person. You have to think of it in terms of making money, anyway. Obviously, the ones which are free downloads attract enormous numbers of downloads, but people will habitually just browse the free sections of both Itch and DriveThru looking for anything free, they will download it, they will put it in a folder, and they may never look at it. So you can’t really count those numbers as meaning actual engagements.

But I find that, at in-person events…if I have a table which has a mixture of fiction and gamebooks, people look at the fiction with a very jaded eye, right? It has to be exactly the book that they want to pick up and read, because there’s a million books they could pick up and read, right? So they’ll look at them and you tell them what is it about, maybe it’ll catch their interest and they’ll buy it, but mostly, eh, they’ll just pick it up and put it back down. Or they don’t even want to do that because they don’t want to engage with the person behind the stall in case they make you buy something.

But as soon as I say “also I’ve got these gamebooks that are like Choose Your Own Adventure or Fighting Fantasy,” people—they immediately make a beeline for them. It’s something different, and often, people I don’t expect to talk will be like, “Oh, I used to love those when I was a child!” Even if they don’t come from a generation where I would expect that to be the case. And people will buy them almost for novelty sometimes, right? Especially the short ones, which sell for 3 or 5 pounds. You’re just like, “Well, this one’s just 3 pounds.” People will just buy them. That’s not meaningful money to them…which means that my boxes of those are empty by the end of the day all the time. It’s not a load of money to them, but I can shift a lot of copies of those.

People just write fanzines and go to zine fairs, right? They’re often selling things at those that are at very low price points. But that’s much easier, to get people to buy that than a full-sized paperback novel, which costs them a great deal more. People are just intrigued, and also they can pick them up, they flick through them, they’ve got pictures… They see the numbered sections and there’s something about that, I think, that just attracts people. Yeah, I do find selling them in person to be easier than selling them online.

Selling them online, you basically have to go to a group of people predisposed to be interested in gamebooks, and then, by their very nature, those people are picky, and are like, “Ah, well, it sounds interesting, but it doesn’t use my favorite dice system, so I don’t want it.” Or, “Oh, it looks good, but I don’t play games with less than 400 sections,” or whatever meaningless pickiness they have. Whereas in person, people who didn’t come in to buy gamebooks buy gamebooks, so, yeah, I like it. I like in-person events.

They’re totally soul-destroying when you don’t sell things! Especially if the stall next to you is shifting all their property like hotcakes. It can be demoralizing when you think your output is decent and then the next person has fifty books that they’ve written, and you’re like, “Oh, I’m so far behind!” But generally I like interacting with the people, and I think giving them that opportunity to intrigue them does make sales.

Of course, the flipside of that would be if gamebooks were insanely popular, that wouldn’t work. They would be treated the same way novels are and people would be totally picky about them and they wouldn’t be interested, but the truth is that’s very unlikely to happen, so probably if you go to either a gaming or a fantasy fiction event, you will be the only one with a gamebook, and people will buy it because it’s unusual. So I think that does work. I think it works quite effectively.

J: One thing I’ve been wondering about with in-person venues is that…I’m in New York City, and there are zine fairs here and also independent comics-oriented fairs. I think something with an art style that might typically appeal to people on Itch more, for example, might be more popular there, because there are a lot of people writing similar-looking things there.

D: Yeah, I think the kind of product you find at zine fairs has changed, and I’ve seen that change in a very short period of time—it really surprises me—which is, it just got bigger. Originally, most zines were maybe ten, fifteen pages. At maximum, they could be eight. The absolute classic random zine is three sheets stapled together, so it’s got twelve pages. Now I go to zine fairs and people are selling perfect-bound comic books. With sixty-plus pages and at a price point maybe in the 15-pound range. Whereas I think of everything in a zine fair as selling for a pound.

There’s a definite shift. People are seeing that they can sell bigger and fancier and more expensive things at zine fairs, and the fact that it’s not really a zine doesn’t really matter. A “zine” has almost become like a stand-in for “small, independently published but not a novel.” So yeah, I’ve taken especially the booklet-sized gamebooks to zine fairs and they’re fine. People buy them. So I agree. I think they will do that.

Comics? I don’t know. I’ve not got a great experience of comic fairs. My impression is always that it’s much more dominated by people whose focus is on the collector market, but I know there’s lots of independent comic creators as well, so I may be just wrong. I just haven’t been to them.

Tabletop roleplaying conventions are also a possibility. A gamebook is another one of these things that sort of straddles that boundary. It’s got dice and numbers, and that’s what tabletop roleplaying has, and there has been such an explosion of tabletop RPGs designed for one person. It’s become a massive thing. Many, many gamers lost their group during COVID and never got them back again. I speak to many gamers who are like, “Oh, I wish I had a group to play D&D with, but post-COVID, that’s impossible,” and you’re like, “Well, it’s not impossible.” People freely mix now. But…somehow they got out of the habit of going to each others’ houses and sittin’ around in groups for hours, and many people just haven’t recaptured that.

So solo roleplaying games are really popular now. Our local game store just has a whole dedicated section for them, because there are so many. And the price point for those things and the complexity of those things has gone up as they’ve gotten more popular.

They started off being one side of A4, and now they’re just big chunky books that you’re sort of expected to sit there and journal with your deck of cards. I’ve done it, it can be fun. In the end, I sometimes find it’s a bit unsatisfying for me because you’re both writing your own story and reading it at the same time, and sometimes you think, “Well, why am I bothering to write it down, in that case?” And then if you’re not writing it down, is it not a bit like daydreaming? That’s the impulse that makes writers go and write stories in the first place, right? (laughs) Then you want someone else to read them! But it’s a big market, and gamebooks fit quite solidly into that.

I think my recommendation would be that the great thing about a gamebook is that you can go to all those venues. If you’ve got a gamebook with a dice-using system and comic booky illustrations, you can take it to the games con, zine con and the comic con, and you only needed one product for all three. That feels like that should be to your advantage.

I’ve only done two of those three. I haven’t taken anything to a comic con, but I’ve been to both tabletop conventions and writing venues and sold in both, so.

J: The only comic convention I’ve gone to was specifically for independent creators, so they didn’t have the box of collectors’ comic books…

D: Right, right.

J: And I think that would be a good place.

D: I think that would work, yeah. I mean, obviously, if it’s the kind of thing that people have a tendency to call “comic cons” but there are no comics, and you’re just there to pay, like, a hundred dollars to get signature from David Hasselhoff, you’re not gonna do well with them there. But yeah, if it’s an independent creator-focused thing, I think that would be just fine.

We have a local thing which is a science fiction and fantasy fiction event, and I’ve sold stuff there, and a gamebook isn’t really, technically, either of those things. But that doesn’t matter. People still buy them.

Crowdfunding

J: How do you feel about crowdfunding websites?

D: I’ve gone off them. But then, partly that’s my own limitations. I’m not good at self-promotion, and crowdfunding is all self-promotion… I don’t think I could crowdfund something I hadn’t already done because I would feel fake promising I will write a thing, and then if I’ve already written it, why am I crowdfunding it? Because it’s already done. To me, if it’s a good product, people should just want to pay for it. This idea of getting people to pay for it, but if they pay you too much, you have to come up with extra stuff they didn’t want to justify why they paid you so much…

I’ve seen really successful crowdfunders fail because they didn’t know what to do with all the money, and I can imagine myself in that situation—I’d have no idea. If I just said, “Aw, I want a gamebook with nicer art, and so I’m crowdfunding it to pay for a printing run and an artist,” and suddenly you made a load of money because everyone liked the subject, what would you do? Give them pins? (laughs) What’s your stretch goals…on a gamebook?

And also, I’ve Kickstarted lots of things and then you never get them. Or you Kickstarted things and you get them, but you get too much. There was a tabletop game, 7th Sea rerelease that Kickstarted. It’s like eight years ago and they’re still sending me supplements because they made so much money. I don’t want any of those supplements. I read the original game and decided I didn’t like it that much, but every month they send me another, like, two-hundred-page supplement, and I’m like, “Uh, that’s nice. (laughs) Stop? Please stop?”

So yeah. I’m mixed. I think they’re great for people, and if the stumbling block is something like distribution or cost of printing or cost of art, then yeah, they’re great. But I don’t see many gamebooks being Kickstarted. Some, but it’s mostly games that have more moving parts, things that need components, maybe.

It has left this terrible syndrome—and this is something I dislike, especially in tabletop RPGs and board games as well—where games don’t exist outside the Kickstarter. The only people who ever own them are the people who Kickstarted them. And as soon as the Kickstarter’s over, the producers aren’t interested in the game anymore, because their real business is in doing crowdfunders. I’ve talked to publishing companies that are just like that. They won’t consider publishing a book unless they crowdfund it because there’s some kind of tacit acknowledgement that without a crowdfunder, no one would want the book? “Well, if no one really wants it, why are you publishing it?” “Well, because people will pay for crowdfunders for products they would never pay for straight up.”

Which is weird psychology and kinda awful. But…it’s true. People will click on a crowdfunder, pry, and they’ll pay over the odds because often crowdfunding a game is a really expensive way of doing it, which if they saw [the game] on a shelf, they wouldn’t part with their money for it.

And so it’s led to this terrible bloat of games that…there’s a FOMO thing where you crowdfund something because you know you won’t be able to buy it afterwards, and it looks good, and if you don’t get it in right now, you’ll never get it, and then… (sighs) I don’t like the whole model. I accept it.

If you’re good at self-promotion, do it, because it’s a great way to bring in income, and it will raise the profile of a project. If you put a post on social media saying “I’m about to publish a book,” no one except your diehard fans care, but if you say “there’s only twenty-four hours left to Kickstart my book,” people who aren’t even interested in your product are following that link, because they see that time-limited thing. Just having a crowdfunder has become a really good way of promoting something. Even if I don’t like it and I don’t really use it, I can’t say it’s bad. If you can crowdfund a product, do it.

It’s a lot less painful than going out and selling it to people individually online, or putting it on Amazon and praying people will notice…and doing the terrible things that Amazon makes you do, like go and force people you know but not too well to buy your book and leave a review, because until you’ve got ten reviews, no one can see the star ratings, and until you’ve got fifty star ratings, your book doesn’t appear in the category listing, but they can’t be your actual friends because Amazon is piratical about removing them if they think they’re associated with you, so all the people who’d like to help you out with a review or your family can’t do it, so then you’re getting comparative strangers to do review swaps—ugh, bleh, it’s horrible.

J: I’ve only had a taste of that, and I didn’t like it.

D: Yeah, it’s—compared to all of that, yeah, do a crowdfunder. (laughs)

But you might find more joy in selling direct to people in person because you actually interact with them in a genuine way. The only problem with that is cash flow, obviously. You can’t go to an in-person event with your product unless you’ve printed it in advance. So you have to do an outlay, and there is a juggling thing of trying not to underprint or overprint. There’s nothing more depressing than opening a cupboard and seeing the stack of some book you printed too many of and didn’t sell, and now it’s just sitting there, and you tell yourself, “Well, maybe someone will ask me for a copy!” But of course they don’t, because even if your friend wanted your book, they would buy it from Amazon before they’d ask you if you had a copy. (laughs) Because that’s what people are like, right?

I have, like, stacks of things where I printed too many, and then I have other things where people do say, “Oh, you should bring some copies of this game to a convention,” and it’s like, “Well, I don’t have any. I sold them all, so now I have to sit down and think, ‘Is this the time where I print another fifty?'” (laughs)

J: That is scary but useful…

D: It’s an argument for smaller books, obviously, that there are economies of scale in, in big printing. So if you print hundreds of things at a time, it gets cheaper. But if your things are small…

You mentioned Heart of Keros, so Heart of Keros is a little bit on the short side, I think, for pamphlet printing. Eh, you’d be okay, maybe, ’cause you’d get fifty sections. It’s not a lot. But I’ve got one: Green Stag…um…oh…what’s the other half of that title?

J: Crimson…Sea?

D: Crimson—yes! (laughs) That’s right! Which I’ve done as pamphlets, and if you’re under a certain page count—especially if you can get your binding done by stapling rather than perfect binding—the cost per copy is vastly less. Also you can get it printed in different places: you can get it from online copy shops as opposed to from dedicated book printers, and they charge you much less, and they don’t care that you’re doing a short order, so you can go to them and say, “I’d like twenty, and I need it here by…Tuesday,” and that’s plausible and you’ll get it, and they’ll charge you (…mental conversion…) about $2 a copy. So it’s not much. But as soon as you go bigger, and start getting perfect-bound, it’s then you suddenly want a whole chunk of them because they’re expensive.

Crafting a New Gamebook System

J: The last thing that I’m curious about is what it was like playtesting the GNAT System. How arduous was that?

D: It was semiarduous.

I had a feel for the numbers. I’ve done lots of games design stuff for both computer games and paper games, and so I had… a reasonable feel for the kinds of numbers and for the dice values. But there was a lot of sitting down and modeling the dice, of modeling, like, how bad a minus-one or a plus-one was. How many points I could give people before it got broken. There’s a great site called AnyDice that does graphing and modeling of dice rolls for you. You can put in things and it will roll dice a thousand times and tell you how often you succeeded and that kind of thing, and that’s really good.

At that point, I also had some other conversations with other designers like, “This is like the core design, what do you think of it?” In fact, the starting value for Talent got changed midway after a conversation with another designer who made a very good argument for why it should be a little bit higher than I put it.

The reroll system…is it Fortune or Fate? Can’t remember. That, that was somebody else’s suggestion. That’s something I’ve used in other systems but I didn’t think it was necessary in the gamebook. But after I’d played a bit and they’d played a bit…sometimes it felt punishing because it’s very easy to get yourself to fifty-fifty on dice rolls, and a single reroll of the dice turns that into a seventy-five-percent chance of success. Giving you that little pool of rerolls is always really good because it means you can have a system with lots of rolls where you expect people to not always automatically succeed, but you don’t have to decide which are the crucial ones. The player gets to say, “Well, no, this is the one where I want to spend points to really succeed.”

The idea of being able to take damage to retain spells came the same way. Originally, the spells were all just one-use, and that was another player-led trade-off, where they can say, “No, I really feel that this is important enough to retain that I’m willing to pay a cost for it.” That’s really good because you put that in a player’s hands and then they can choose the important points.

Yeah, I didn’t think it was painful, but you do have to do it. You have to write some adventures using your system and then…play through them yourself a lot with different characters to see how awful it is.

One of the things I always try very hard to do with the GNAT adventures is have an even distribution of all the skills, because it’s very easy to think of lots of uses for, like, climbing… Swimming always gets left out, right? No, every adventure needs swimming. So you’re like, “Well, I’ll try to find some use for swimming. Try and not put in too many uses for climbing.” That’s been really nice. That’s why there’s always been something to do with your Nature skill. There’s always an animal to observe or a herb to pick or something because I want that to be important. There’s always something to decipher so that Linguistics isn’t ignored.

I take care to do that even spread. Or occasionally some of the adventures do, in the introduction, say that you’re not gonna get any use out of this skill, and I put that in the front so that people don’t feel they were “fooled” into making a terrible character. That kind of reduces that design constraint a little bit. You don’t always have to have even numbers of skills if you tell people up front, “Sorry, we’re not using Nature this time ’round.”

So, not painful, but necessary, I think, is the answer.

J: Was it important to have other people playtest it?

D: Yeah. It’s really important to have someone else play the adventure specifically because it’s very easy to make assumptions. Gamebooks are often puzzle-related. You’ve got to go and do the right things in the right order, and sometimes that’s really clear to you, you give it to someone else and they’re like, “I don’t know why I’m doing this, I don’t know why I’ve got this item, I don’t know what to do now.”

I think any bit of writing really benefits from other people reading it, but I think a gamebook is also a puzzle. You can’t get a short story “wrong” in the sense that someone can’t get half through the story and get stuck…but in a gamebook, you can get stuck. The number of times someone’s said to me, “I went into this room and there isn’t an exit,” and you’re like, “Oh…oh, you’re right! I just…never put the exit in!” It’s easy to forget that kind of thing.

Getting other people to play through your stuff is important, which means you’ve gotta find some gamebook enthusiast who wants to do that, but…luckily, I know a few (laughs) so it’s okay. And no doubt if you do something, they can be persuaded to also do the same thing.

J: I definitely have writing friends…I mean, we collaborate on things, just not gamebooks, but I think that might be possible.

D: I find writing people are…they’re good for the introductions to a gamebook, the bits where you’re setting the scene because that’s more like prose, but if I go to just normal writing people and say, “Well, what do you think of this room?” they’re a bit nonplussed. They don’t know really what to do with those little snippets of writing, and they don’t play through the game. So I think you’re better getting it playtested by someone who’s more of a gamer first and a writer second because you want people to tell you if the game works.

Some gamebooks are very badly written in terms of prose, and I’m not sure people care? If the adventure is fun and the structure is good, I don’t know if they care as much about the prose. In a way, that’s the more important thing to test, maybe.

A few months after this interview, when I was formatting and preparing to post it online, I reached out again with a brief final question:

J: What are you [currently] working on? Also, is one of those things Lindenbaum?

D: I didn’t enter Lindenbaum this year, no. The collaboration that I mentioned in the interview came about, and I’ve spent a lot of time on a very expansive (500+-section) CYOA adventure based on every folk horror trope you can think of.

I’m also putting together a second collection of short fiction.

Thanks, David, for letting me pick your brain! Follow him and find all of his work at teuton.org, and please stop numbering your CYOAs by hand!

For more from me about gamebooks and solo gaming, click here…! Or take a look around. There’s kind of a grab bag of stuff here.