LitRPGs are like books plus video games. And while most websites defining them will assume you already know a lot about video games, I’ll pretend you’re my mom, who hates them and has no idea what kinds of books I’ve been editing for the past several months.

This explanation will be slow and methodical.

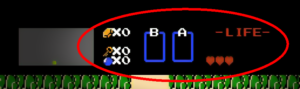

First, let’s look at an actual video game. Here’s a screenshot from the game The Legend of Zelda.

Everything up here that I’ve circled represents something that the main character can do. We can see he has 0 gold, 0 keys, and 0 bombs. If he had gold, he could buy things; if he had keys, he could unlock doors; if he had bombs, he could use those to destroy walls. You get me. Don’t worry quite so much about that part, or the B and A boxes in the middle (that represents what the character is holding in his left and right hands, like his sword and shield, for instance).

Rather, pay close attention to the right side. Our dude has 3 heart symbols that represent his Life. Every time he gets his by an enemy, he loses 1 of these hearts—meaning if he takes 3 hits from enemies, he has no hearts and he’s dead.

This is all information that the player sees at all times. It’s always at the top of the screen. But in the fantasy world of the video game, those numbers are not supposed to exist. In other words, we’re not meant to imagine the protagonist saying, “Gee, I must be injured, because I only have 1 Life heart left. I better pick up one of those blue orbs I’ve never seen before, yet know I can have in my inventory.” Real people do not have health represented by hearts!

No, these hearts and numbers are just abstractions for the viewer’s benefit. We can’t see how badly this character is injured, let alone feel it, because technology is limited (and very few of us want to feel the wounds of a video game character anyway).

But in LitRPGs, this information is also real in that fantasy world. We’ll circle back to what that means in a moment.

Roots of LitRPGs

The name “LitRPG” comes from “literature” and “RPG,” or “role-playing game.

For decades there have been fantasy novels with elements inspired by or borrowed from not only the tabletop games that introduced the term “RPG” (most famous among them Dungeons and Dragons), but also video games (like The Legend of Zelda above). But as you can imagine, 99.999% of these books are not LitRPGs. Maybe the spells that a wizard hero uses are inspired by the spells that a wizard can learn in Dungeons and Dragons, but unlike players of that game, this wizard is not stopping every ten steps to roll dice in order to figure out whether their spell hits a flying spider or not.

And although a warrior might find the Master Sword like heroic Link from The Legend of Zelda, that warrior is not marveling at how grabbing the Sword automatically refueled 8 Life.

Until now.

Well, okay, I’ve never heard of a LitRPG protagonist rolling literal dice in the middle of combat, but the latter scenario does happen. Heroes will be fully aware of the numbers that say what they can and can’t do—their stats.

But how and why did people start writing this?

LitRPGs are a very recent development, but I can’t claim to know how recent. I do know one point of inspiration, though.

One type of RPG that could only have developed with the rise of the internet is the MMORPG, whose name stands for “massively multiplayer online RPG.” What’s important about these games for our purposes is that in most MMORPGs, you aren’t playing “Link the hero,” “Billie the wizard,” or any other premade character. You are playing as “yourself”—a character you design. And when you talk to other players in this massive multiplayer game, you can speak in your own words. This is a level of interactivity that a premade hero with a premade script could never do (and indeed, the classic, old-school video game hero has no dialogue, doing whatever the quest-givers tell him to do).

In an MMORPG, the player is the hero. An effort is made to immerse the player in the world, even though it’s digital. But this has an unintended consequence.

A real video game protagonist would never be able to see their own Life total. But a player needs to see that total, or else the game won’t be fair because they’ll have no way of knowing how close to death their character actually is.

So the player needs to see their own stats. And the player needs to act very unrealistically.

The LitRPG world really comes from this idea. It’s a place where day-to-day survival takes the kind of strategic planning that nobody would use in real life, but the best MMO players would use to get ahead in a game setting. The result is often fun, often nail-biting escapism where the stakes tend to be extremely clear. You’re not “struggling to breathe,” you have exactly 1 Life remaining.

And for people who’ve played a lot of video games, the settings and tropes are often familiar, easy to jump into. I don’t know how the criminal justice system works, and I’m not a socialite who can relate to the small-town goings-on of most quirky detectives, so the type of thrill I would get from a typical thriller or mystery is changed, in some ways hampered. A LitRPG is different. When the setting is known and readers have a broad idea of what can happen, they are freed to hone in on the details and see which ones the author twists. Usually, that twist is about strategy. When the world is numbers, those numbers are often exploitable. Anyone who knows how to change those numbers, or use a clever gambit to work them, is king.

If you ever hear about a character having a “system” in a LitRPG, that’s referring not to their successful study habits, but to these interlocking stats, all the numbers and variables that tell them what they can and can’t do. All these things together can be referred to as a system. When characters view and interact parts of the system, they tend to act like video game menus. They might say “Life: 3,” but also things like “Keys x0,” “Secret Unlocked,” and “Game Over. Would you like to restart?”

What does it actually look like in a novel?

Kind of awkward, honestly?

Some LitRPGs are more intrusive with numbers than others, and some people hate numbers that are too frequent while others actively seek out the most number-filled. Either way, it is blatantly unnatural. It takes getting used to. Here’s an example I just made up where the statistics are more intrusive and heavy:

I dove into the fray, swinging my sword through a flock of Dread Geese.

Dread Goose #1

0/5 LifeDread Goose #2

0/6 Life

BONUS: Dropped Goose Feather x5Dread Goose #3

0/4 LifeDread Goose x3 slain!

+330 Experience PointsAs I landed, I scanned the text box that had appeared before me. Wow, that gave me more Experience than I’d expected. If I could get to the next level before sundown, that would put my Strength over the top—and I would need every bit of it for tomorrow’s battle.

And here’s a lighter version:

I dove into the fray, swinging my sword through a flock of Dread Geese. As the monsters perished and disappeared, they left behind five Goose Feathers, and my Experience ticked up by 330 points. Wow, that was more than I’d expected…

One enormously popular LitRPG on the lighter side is The Wandering Inn. This one is so popular I’ve seen it discussed in an average Creative Writing class. Generally you’ll find an amazing variety of LitRPGs free to read on RoyalRoad—the list of most popular stories on this platform is dominated by the subgenre.

Thus Ends My Presentation

I hope that anyone confused by LitRPG definitions that start by saying things like “LitRPGs are stories inspired by MMOs and Sword Art Online…” found some greater clarity here. Please leave questions and show me anything I missed in the comments!

I am, predictably, working on a LitRPG story of my own. I’ve also been theorizing about how to craft one, because I would love to see more blog posts about how different people go about writing different types of LitRPGs.

But I also discuss other stuff, like drawing comics (with limited art skills) and writing about wartanks for its own sake. And The Cowboy Way (1994).

“Well, okay, I’ve never heard of a LitRPG protagonist rolling literal dice in the middle of combat,”

I didn’t realize it until reading this sentence, but, this is literally Vriska

Homestuck is “more LitRPG than LitRPGs” insofar as game mechanics are interwoven with the story and incredibly diverse. As long as we’re here fucking around, it’s also an isekai with additional layers of isekai (dream bubbles + God Tiers + Hiveswap whenever Hiveswap finishes). Vriska Stinks!!!!!!!!