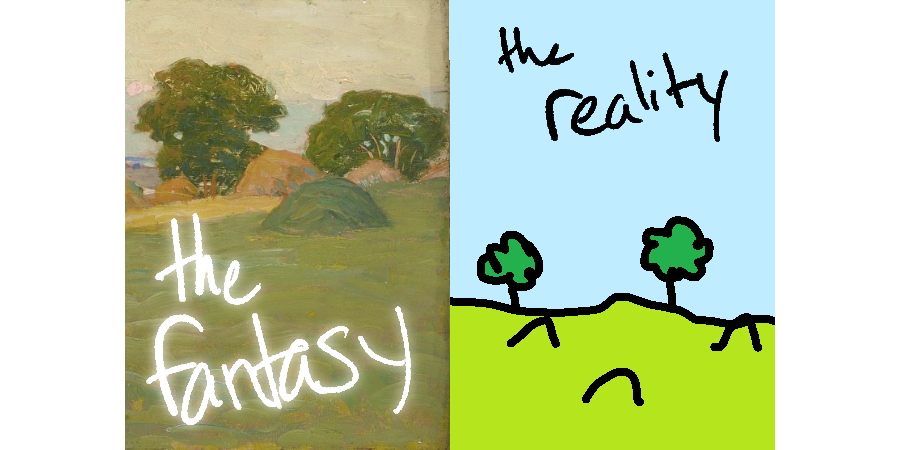

“I’d love to make a comic. If only I could draw…” Stop right there, buster.

Anyone can draw. Not everyone can make a still life—not everyone can hold a pencil with perfect poise—but everyone can get marks on the paper.

People seem to think I’m a great artist. Yes, I can cartoon a little. But I cannot do a still life, and perspective makes me nauseous. So I would call myself a good artist but nothing more—and that’s mostly because I doodle a lot. (Practice doesn’t always make perfect, but at least I’ve made something.)

Start seeing yourself as a good artist—someone who is good because they try. Then you’ll start feeling good about your artwork.

This is not a guide to great art, to masterworks. But think about your own needs. If you had your own comic, would you need it to look like Picasso? Or would it be enough that you’ve gotten a dream down on paper?

Instead, it’s a guide to producing something you will like. Something you can show to friends or strangers or anyone you want, and feel good about.

Making art is hard, especially for beginners. There’s no shame in taking it slow and easy.

Learn the Tools You Have

By “tools,” I mean…

- Your drawing utensils. Okay, so most professional comic artists will use fancy fountain pens or expensive digital drawing apps. Imagine you go out and buy a fountain pen, only to burn out in frustration after a week of failing to understand it—you took the new technology and flew too close to the sun. Start with what you have. Start with your pencil and Microsoft Paint.

- Your time and energy. You may only have a few minutes every Monday to work on comics. So be it. All the time you spend away from the comic is time spent “sleeping on it.” In other words, your brain will keep working on it in the background—sometimes springing to the fore with a sudden epiphany.

- Your mind and body. Many artists have disabilities. These aren’t experiences I can personally speak to, but if you search for “artists with…” or “artists who…” you’re sure to find people. Pencils don’t need to be held with hands. You might not even draw—why not scrapbook or collage? You can work with photos, too, including open-access photos that others have taken.

- Your preferences! What you like and dislike. While you can always learn to love new things, some ideas almost feel innate. They stay with us forever. Which brings me to my next point…

Doodle…A Lot

Do you love a blank canvas, or fear it?

Some people have no trouble pouring out ideas. Others can’t even start. And several of us need the right mood—whether immaculate calm or methodical rage.

As an artist (which is what you are), you’ll get quite familiar with blank pages. My suggestion is that you practice filling them up as much as possible. And that you free thyself by drawing free form, jotting out free thoughts. Creating “nonsense” that, when you come back to it the next day, actually turns out to inspire you. Today’s sketch might be tomorrow’s punchline. It might be an objet d’art in the background of a panel.

Kids draw things that, to the untrained eye, look like a bunch of nonsense. Kids are extremely creative. Lots of them have no trouble hashing out comics and now you, too, can have that power.

If you need help relaxing, here are a couple of drawing exercises for that:

- Zen doodles. Drag your pencil around on the paper—without lifting it—for as long as you please. Then color in the shapes you’ve made.

- Wavy lines. Make a line like a big, curvy soundwave. Just keep moving your pencil up and down, up and down, across the paper.

These don’t just calm people down. Making big, loping shapes on your canvas can actually help prime you for drawing. I’ve seen artists recommend drawing a few minutes’ worth of wavy lines (as well as circles and straight lines) before getting down to business!

Get Specific: What Do You Want to Draw?

This is for all you methodical types.

Maybe you want to make a phantasmagoric, different-every-day graphic tapestry. That’s amazing! You can take the “Free Thyself” step above and run with it.

But what if just doodling isn’t enough? Perhaps you have an epic fantasy narrative and you’ve known the ending for five years—or you know that every issue takes place in a single garden. Perhaps you imagine all the different weapons or flowers you’ll have to draw and your spirit sinks.

Take a new approach. Think, in clear and unambiguous terms, of all the things you’ll have to draw. Start a list. Or start many lists for many locations.

Don’t leap in too fast. Don’t just run down that list learning how to draw each one.

Instead, simplify.

- Cast of fifty characters? Don’t expend so much energy trying to make each one look both distinct and realistic. What’s important is that they’re distinct. Heights, haircuts, outfits, color schemes—these can all help. Maybe the only difference between two brothers is that one wears bigger boots. That works.

- Galaxy of weapons? Streamline it. If you can spare a few, then spare them.

- Hundred-plant garden? Fretting over how much your roses look like your peonies is probably not helpful. In fact, you might want to make your flowers more similar. That means fewer new shapes to learn to draw. Again, consider marking differences not with the flower’s exact shape, but with other factors—color, stem height, location, context (like a character remarking on the beautiful peonies).

Yes, challenge yourself when the challenge feels energizing. But don’t keep running when you’ve hit a wall.

Few newspaper comics take place in a variety of extravagant locales. They exist in a handful of simple, ordinary spots. If your comic is about a girl and a dog, you might only have two locations: the house and the doghouse. And there’s no need to get elaborate. (Do we ever see Snoopy’s doghouse from more than one angle?)

Why do I only draw backgrounds for StarCrash!! with Jeff once in a blue moon? It’s because…well…I can’t draw backgrounds. And I kind of hate to draw backgrounds. So for about 5% of the comic, I really slow down and draw trees, rocks, mountains. For the rest of it, I draw white voids and buildings that look like baby blocks.

But for my story, the characters and writing are more important than the backgrounds, so that’s what I focus on.

Study What You Love

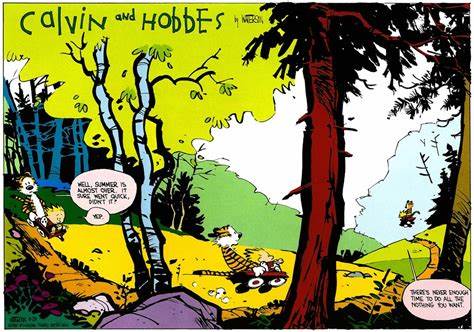

A classmate from my art class said that he gets his trees from Calvin and Hobbes.

We’re not advocating for stealing. We’re advocating for studying the techniques of artists you admire.

Of course Bill Watterson is a trained artist who brought years of experience to Calvin and Hobbes—and, of course, it shows. But you don’t have to copy his work note-for-note. You can borrow here and there.

Take a look at this…for me, these trees strike a balance between realism and simplicity. I like it. I want to try it.

Here’s me doing just that with my non-dominant hand:

I didn’t even notice the tree bark was BLUE until I did this. Neat, right?

You can study—and borrow from—any work you come across.

You don’t have to borrow everything from the mind-blowing landscape of your favorite AAA video game. Instead, notice how its ruins blend with its grasslands. Take that bit. You don’t need to copy this actor’s period costume. Copy the sleeves and simplify the collar. Look at what you love—and reinvent it.

Remember, artists do this all the time. We just don’t talk about it because we don’t want people to think we’re stealing.

By Trying, You Have Already Won

Do you know how many people are walking around with “that one golden idea” in their heads—and how many put zero percent of that idea into the world?

Let’s say you use this guide to help you jot down comic ideas for a few days. And then shelve the idea, deciding it just doesn’t feel right.

Well, you’ve already come out ahead of most people. They’ve put out zero percent, and you’ve put out zero-point-one. You got your own ball rolling.

Even if you never finish, you’ve done what once was impossible.

Thank you for reading, and Patrons, thank you for Patreonning.

Do you have any other tips for good, scrappy artists? Is there anything I’ve missed? Let me know in the comments! And when you’re good and ready, check out my reflections on how to make art even after you’ve lost the momentum, what it’s like to self-publish a super-small comic, and why so many people have loved a certain super-long book series about a certain wizard boy.