Why does nobody talk about this ambitious, high-octane, bizarrely stylish manga?

When I was in high school, seinen and shōnen manga (especially edgy ones) were my favorite things. Hunter x Hunter, Parasyte, Attack on Titan, Death Note—all series I devoured. But what manga felt like full-on events? I can only think of two: Akira and Ultimo. Akira has such an impressive pedigree (and such a huge print size) that buying it can’t not feel like an event. But all Ultimo had was suspense and promise.

It also had Hiroyuki Takei and Stan Lee, but trust me, I didn’t care about that.

Hiroyuki Takei created Shaman King, one of those battle manga that wasn’t too popular but wasn’t exactly unpopular, either—a mainstay. To this day, it has a number of continuations and spinoffs that I find disturbing. I’ve been familiar with Shaman King since I was a kid, but I never got into it.

And Stan Lee, since he injected himself into so many projects that many Americans know him without even trying, probably needs no introduction. I never read Marvel comics, but I first witnessed his goofy persona through the SyFy show Who Wants to Be a Superhero?—and just in case any of you remember that show, I’m gonna go on record as saying that Hyperstrike should’ve won Season 2 and they did Feedback dirty with that cameo in Mega Snake where he got eaten after about five seconds.

While neither of these were selling points to me, they did admittedly give Ultimo an aura of grandeur. And they must’ve been selling points to lots of people. Heaven knows the publishers tried to make this story big, with Lee and Takei even appearing together at comic conventions to promote it.

But why does nobody seem to care? I can find a few retrospectives online, but I’ve never seen someone dive into the whole 12-volume series, beginning to end. That’s my mission today: to finally finish this story that was near and dear to my adolescent heart.

(The fact that I didn’t read past volume 8 back then should tell you something.)

First Impressions

The setup: two mechanical boys called dōji, one pure good and one pure evil, are destined to fight to determine which force is greater in a terrible battle called the Hundred Machine Funeral. But until then, they must collect more information on what good and evil truly are by serving different masters throughout time and space.

Is this concept worn-out and cliché, or tried and true? I dunno, I always liked it. It definitely evokes a whole hodgepodge of hit manga. On one hand, there’s Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy and Buddha, but especially Phoenix, with its focus on reincarnation across the ages. On the other hand, there’s the more modern Zatch Bell, where one hundred demon children (see that number, “one hundred?”) fight alongside humans to decide their next ruler.

And now that I’m reading it at the age of twenty-something, I can’t help but wonder what Ultimo would be like if it targeted an older audience. I mean, gee, I’ve loved Naoki Urusawa’s work for a long time—can you imagine Pluto (more mature take on Astro Boy) plus Billy Bat (weird historical conspiracy mystery) with a dash of Monster (hard-hitting moral conundrums)?

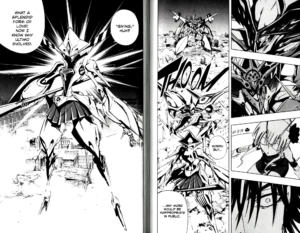

But when I was just a beanballheaded teen, this concept felt startlingly original to me. The reason it felt that fresh, I believe, is the art: angular, crisp, shining, almost translucent with its fine, broken lines. I’ve never seen anything that looks quite like Takei’s work from late Shaman King onward (and I find it fascinating that his style went from thick-outlined squares to these flimsy triangles).

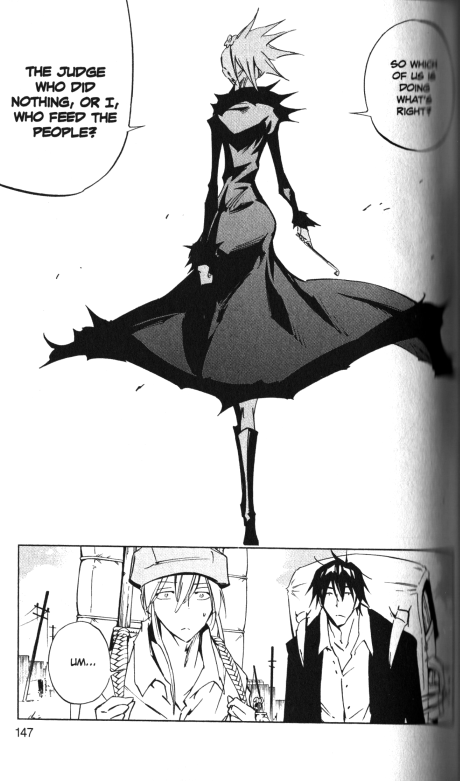

I’m shocked that some people find this manga genuinely ugly. I concede that some action scenes can get hard to follow, with robotic parts blending into each other. I concede that characters are weirdly thin and you can sometimes see every single rib. I concede that a few characters have breasts that appear to be growing out of their shoulders. But come on! At least respect it for its uniqueness, for how extreme and gutsy its aesthetics can get.

The story starts humbly. In 12th-century Japan, an eccentric traveler who looks suspiciously like a Stan Lee with long, luscious locks reveals Ultimo and Vice, pure good and evil, to a band of thieves. It’s a well-executed first chapter that transitions into the modern day as the reincarnation of the thieves’ leader, a high schooler named Yamato, must teach and fight with Ultimo whether he wants to or not.

I like this guy! He’s a brusque loser whose cool moments are balanced out by his general goofiness. His cousin is probably No More Heroes’ Travis Touchdown. He makes a great partner for Ultimo, whose natural state is bubbly and overeager—until he enters combat, becoming an unholy terror whose ideas of goodness may be dangerously flawed.

Since this overview will focus on the plot much more than the characters, I’ll give bullet points to a few key players:

- Vice, the strongest evil dōji and Ultimo’s counterpart.

- Rune, Yamato’s best friend who resembles Shaman King’s Manta with glasses.

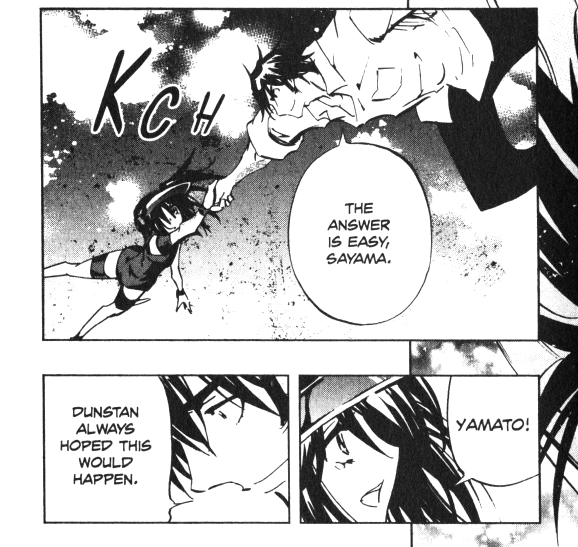

- Sayama, Yamato’s mysterious love interest. She treats him kindly but seems to have no awareness of his delusional crush on her. (And I do mean “delusional”; it is implied that Yamato is thinking about Sayama every waking moment of his life. I…dunno how to feel about that).

- Eco, an early ally. He’s an average kind-hearted family man…with a dark side?

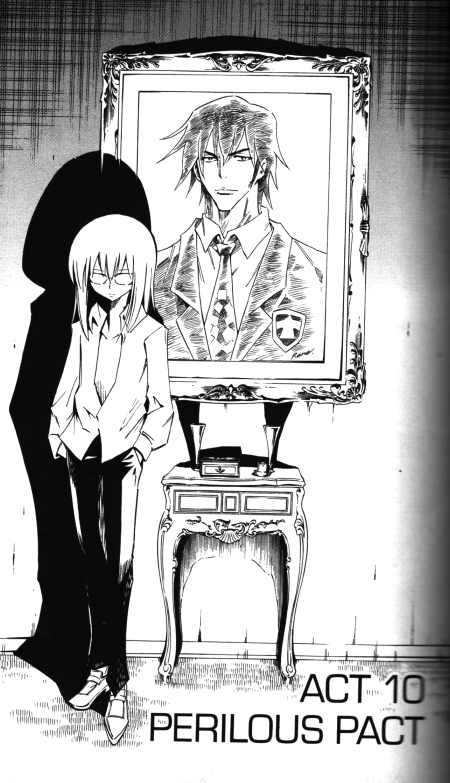

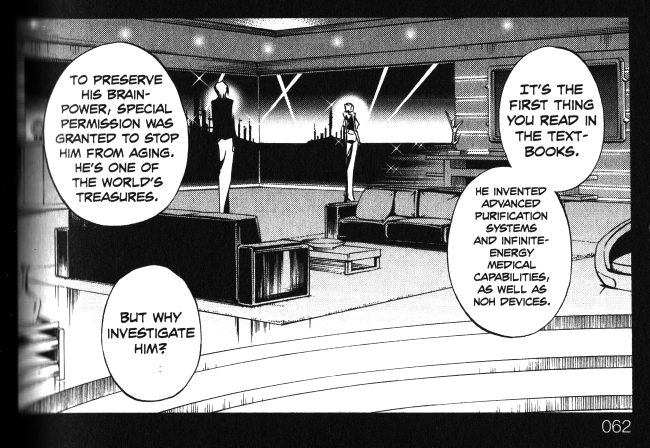

- Dunstan, the Stan Lee-like, time traveling, luxuriously maned purveyor of dōji.

The first two volumes gently raise the stakes and gradually introduce new cast members. More rival dōji and masters appear, setting the groundwork for a wonderful episodic morality play. In my opinion, the first matchup that really shows that Ultimo has promise—that it can discuss morality and investigate its characters with interesting nuance—is the battle with Jealousy and his master Iruma, a politician who proposes, “Sell me Ultimo!”

Yet the manga seems determined to present not just a high-quality shōnen manga, but an unpredictable and truly explosive experience.

From this point onward, there will be spoilers, so read at your own risk…or click here to skip to my final thoughts.

Accumulating Promise/s

The first two promises this story makes are…

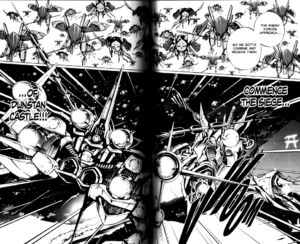

- That there will be something called a Hundred Machine Funeral. Now, we don’t know exactly what this means, but it sure implies that there will be a hundred different dōji killing each other.

- That reincarnations of the main characters in the past, present, and future will be pivotal.

These are tall orders. The first promise means that if readers don’t see one hundred dōji—if they don’t at least get a believable impression that there were at some point a hundred dōji, with some killed offscreen—then there will be disappointment.

The second promise, in theory, means that every single character has three important variations, but in practice that’s not necessary—we just have to get a few reincarnations in every single era that truly count. But this is more of a logistically messy problem than anything, and I’ll tell you why.

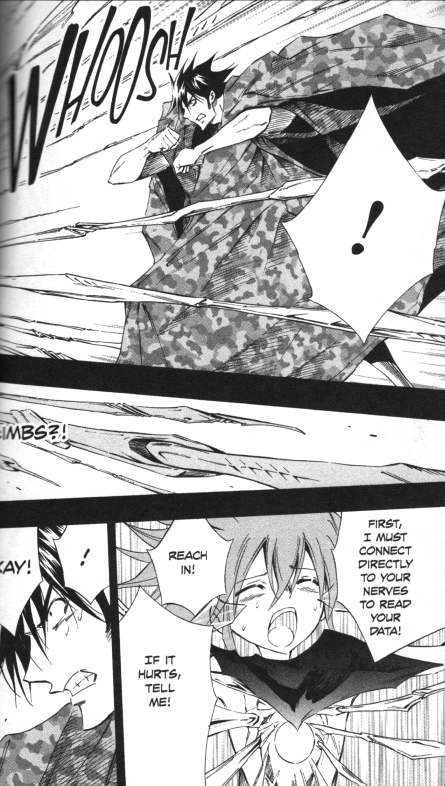

In volume 3, Yamato and Ultimo get their first power-up in the form of the pledge. Ultimo claims that through the pledge, Yamato will regain all of his memories, across all eras. Now, that’s a logistical nightmare that implies that Yamato’s gonna spend the rest of the series with a galaxy brain, but as you might guess, the story has convoluted ways of ensuring that doesn’t happen.

One of those ways is by making Ultimo’s claim not just a little false, but actually extremely false. At least the story soon reveals that Ultimo consciously withheld memories from Yamato—which is a great twist in my head, but it also raises many questions, such as: how did Yamato not notice a huge gap in his memory from the ancient times when he was a healthy, strapping thief guy? Also, if he apparently gets memories from the future, why does he never scan through any of those memories except for one of Dunstan as a mechanical dragon (more on that later)?

So that’s a third promise—that anyone who pledges gets all their memories from across time and space—that got busted wide open. The main thing it led to was impressive-looking splash pages. Disappointment!

And this is why Ultimo doesn’t get talked about. It has such an endearing beginning, such strong early moments, and such cool-looking gauntlets, but the expectations it sets are untenable—and it makes too many. In hindsight, these promises read more like desperate ways to keep readers hooked than paths to genuine payoff.

When I was a beanballheaded teenager, though, I didn’t realize this—I just went along for the ride. So the end of volume 3 hit me like a well-executed truck, even though it turned out to be another one of the story’s biggest mistakes. As Yamato and his former best friend (!) battle in the wilderness, piloting dōji who have now become giant fighting robots (not as cool to me as boys with gauntlets, but okay), the other good dōji who have been introduced so far come to the rescue and show off their cool forms (!!), only for a heap of bad dōji to show up too (!!!) and defeat everyone (!!!!) in what turns out to be the Hundred Machine Funeral (!!!!!) so that Yamato has no choice but to expend a huge amount of Ultimo’s power to go back in time and set right what once went wrong (!!!!!!!!!!).

“It has begun,” says Dunstan, who is mysteriously able to observe this massive destruction. “Destruction of the Earth’s magnetic field by a distortion in space-time.”

Just like that, we are now suddenly in a timeloop story.

50% of readers probably dropped the story at this point, but I was part of the other 50%. We were practically ride-or-die.

Off the Rails Again and Again

There comes a point in certain shōnen manga where things have gotten so tedious that no matter what the story throws at you, you just can never get excited anymore.

Exactly which manga those are will vary from person to person. In my opinion, the most painful ones to read aren’t the stories you never really liked from the beginning (like Shaman King was for me). They’re the ones that you used to like.

The great manga tragedy of my age was Bleach. Now, I heard that some young folks don’t have any idea what Bleach is, because it stopped running and it lost much of its cultural relevance. (I would add something derisive about people not looking back at the classics, but let’s face it, is Bleach even “a classic?”) This manga was one of the “big three” shōnen manga of the 00s, rivaling One Piece and Naruto. Depending on who you ask, it got tedious somewhere around volume 9 or 50. For me, the Hueco Mundo arc starting at volume 20 was the point of no return. Sure, it still had good elements, but I just got the sense that it would never be as smooth or coherent as I wanted it to be ever again.

Fatigue! That’s what Bleach eventually made me feel and what Ultimo much more quickly made me feel. Past, present, and future combine. Okay. There’ll be two hundred main characters (a hundred dōji and their masters). Okay. Timeloop. Okay. We’re going back in time again to go into Iruma the politician’s past, on a journey that turns out to accomplish nothing except for the fourth battle to date with Jealousy and the official introduction of Dunstan.

Somehow that was still okay.

When these promises and twists were first coming out, I didn’t know how bad the story was going to get. Ultimo still could’ve had a come-from-behind victory. One of the reasons Bleach’s Hueco Mundo arc was so immediately tiring to me when I reached it was because I had heard so many details about it already, including rumors of how it dragged and how its tons of new characters so often fell by the wayside. But my sibling was buying Ultimo as it released. Therefore, it was a big event and the outcome was unpredictable, meaning its true badness was obscured by sheer excitement.

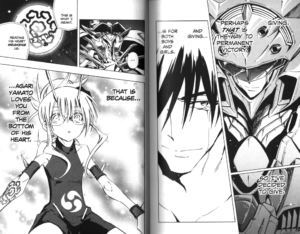

It is soon revealed that the timeloop meant to curb the Hundred Machine Funeral was only a one-time thing—Yamato had to go set right what once went wrong, but it turns out that no he doesn’t, because Long-Haired Stan Lee (officially known as Dunstan) comes in and explains that the official rules for the Hundred Machine Funeral are different from what everybody assumed. It’s not a bloodbath; it’s a battle of changing hearts. Ultimo and his fellow good dōji, the Six Perfections, must convert Vice and his Seven Deadly Sins to their side to win—before evil gets them first.

Why didn’t Dunstan explain that earlier? So we could have more drama. Oh, also, the Hundred Machine Funeral is now supposed to last a year.

That is a huge tension killer. And it’s a promise killer, not least because it reveals once and for all that there are only 15 dōji total. So by volume 7 when these new rules are made official, readers have been introduced to every dōji already, which severely limits how surprising Ultimo can be. (Wow, that’s like the exact opposite of the character problem that Bleach has—Tite Kubo made way too many characters, and would famously throw in new ones whenever he was stuck for where to take the story next.)

Even in this janky midsection, though, Ultimo is still capable of good character-based surprises. Standout moments include Yamato’s conversations with Eco—the way their backstories intersect both caught me off-guard and warmed my heart. The series also has plenty of fun character twists for those who’ve been introduced—for example, when three of the original dōji masters fall, Yamato’s mundane classmates are suddenly tossed into the maelstrom.

Yamato and Ultimo also have fun and interesting interactions—but we see less and less of the title character as the story goes on, which is another real shame…but I have a lot more to say on that.

Pretty Kid Optics

This section mentions pedophilia. (While Ultimo includes no sex scenes, it has suggestive imagery.) Click here to skip to the next section!

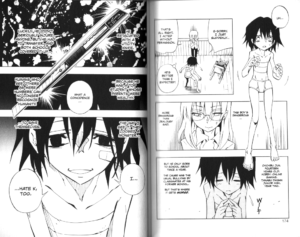

Okay, let’s get away from the tangle that is Ultimo’s main plot for a while. Can we talk about how Ultimo looks? Again? (I actually wrote a separate blog post musing on his femininity and the general in-universe acceptance of it—how he’s “girly” but not considered less cool or capable for it—that leaked beyond the bounds of this review.)

Another one of the coolest things ever, in my younger opinion, is his appearance. The huge hair. The visor-like things on his head shaped like fawn’s ears. The doll-sized eyes. The impossibly huge, flowing pants. “Ulti,” as he calls himself, is an extremely cute living weapon with a creative design that gives his story much of its identity.

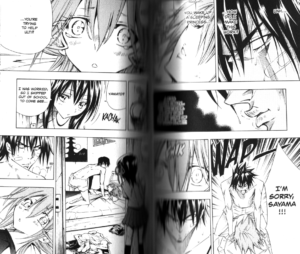

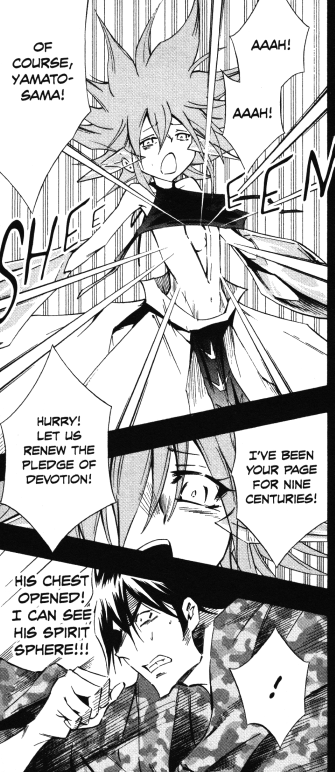

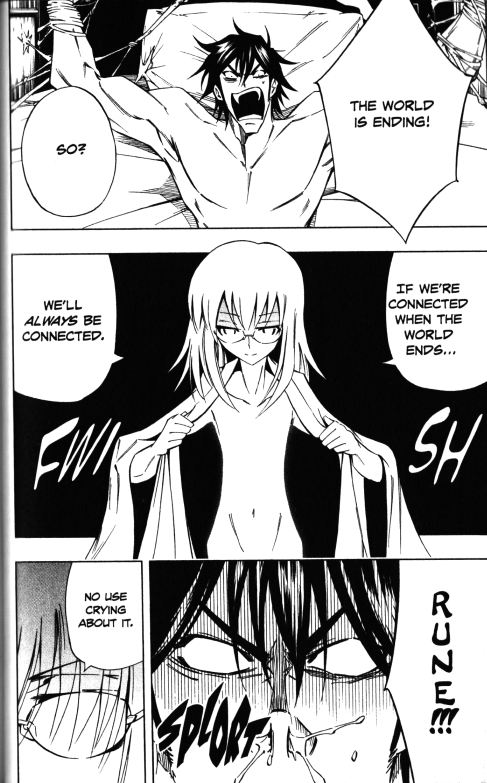

Also, you can see a lot of his stomach, and considering that he’s a mechanical boy, that is, perhaps, kind of weird. Then again, Astro Boy and kids wearing swimsuits show their midriffs, too, so that’s not unusual. Oh, wait, Yamato just got caught in bed with Ultimo, posed as if ready for sex, and it was played for laughs…oh, wait, Ultimo’s pledge with Yamato is explicitly sexualized (he removes his shirt, then cries as he says, “If it hurts, tell me!”)…

I totally lack the credentials to give you an analysis of what Ultimo’s presentation means or is intended to mean for a Japanese audience. I’m going to focus entirely on its effect on me as a beanball American high schooler and what I imagine might be its effects on others.

Really, it’s nothing new for manga, in the late 00s or now, to show relationships like this that are—if I had to describe it—not just skirting the line of showing pedophilia, but gleefully dancing back and forth above it, insisting, “I’m not touching it, I’m not touching it!”

See, Yamato was in bed with Ultimo, but we know he didn’t mean it that way, which apparently makes the scene fine! Ultimo didn’t really have sex with Yamato, it was just symbolic and metaphorical and it meant something way different, which apparently makes this fine too! And when one of the villains—K, Vice’s master and a pervert NEET guy (since pervert NEET guys are what this series defines as the ultimate evil)—stalks a main character who is a child, we are expected to laugh! Because it shows that K’s pathetic, get it? Isn’t it funny how pathetic he is!

What was the effect of this “see, it’s not really pedophilia the way you think it is” imagery on me as a youngster? I honestly didn’t think about it; I was so used to it that I never analyzed it and it became invisible to me, which I believe is dangerous even when the scenes are indirect, comical, satirical, or metaphorical. And particularly if most readers, who come for the cool fights and aesthetics, aren’t necessarily inclined to suss out any of those nuances.

My conclusion here is basically: shouldn’t it be weird to put things like this in an action series marketed to teens?

Speaking of suggestive scenes, I haven’t even talked about Rune yet…

Rune and “Scary Gayness”

This section mentions attempted rape and LGBTQ+ demonization, so click here to skip that too.

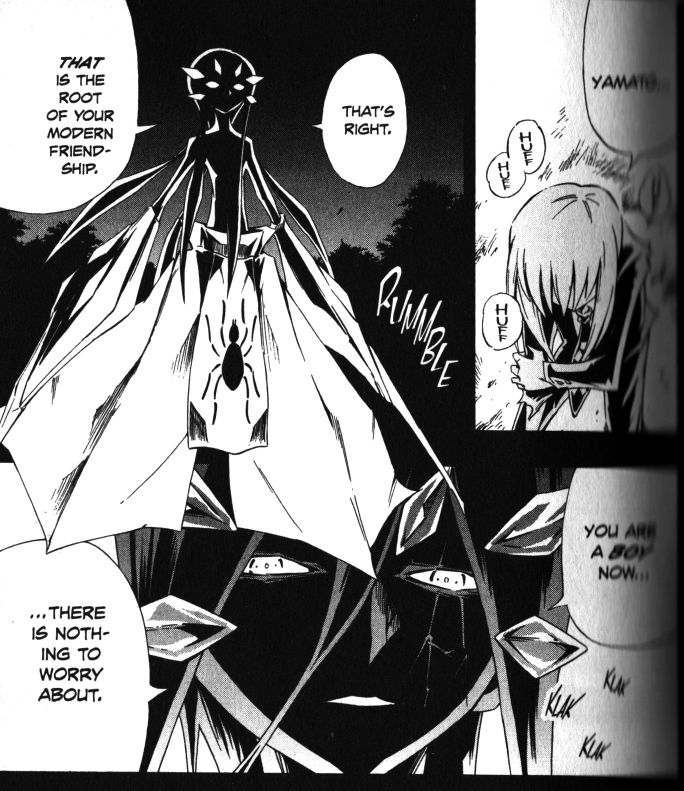

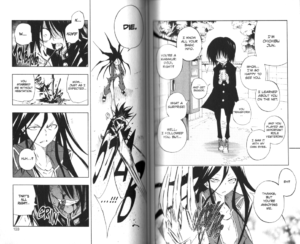

One of the first huge plot twists of Ultimo—which sounds good on paper—is that Yamato’s best friend, Rune, is actually his reincarnated lover. This is a problem because, for one thing, Yamato is doggishly in love with his classmate Sayama. For another, in the span of a reincarnation, Rune has gone from a princess to a boy.

I think there are several ways in which this twist could have been written with nuance and grace. Actually, there are many moments when Takei draws and writes Rune with dignity, and when he successfully gives Rune much more to do than just remember his love for Yamato or desperately yearn for Yamato. No, Rune is one of the more fleshed-out characters in a series that is hurting for deep characters. He’s a smiling schemer, quietly delighting in pitting the factions of the Hundred Machine Funeral against each other in new ways.

But he’s so bound up in his exploitative rapist-stalker-creep imagery that it’s very hard for me to give any points for that.

Besides that, there are just enough repetitions of phrases like “you’re a boy now, Rune” to not only make my gender-questioning self uncomfortable, but also make me ask myself the natural logistical question: if the dōji masters have all taken the pledge by now and can see their future memories, why can’t any of them remember gay marriage?

Of course, the more plot-relevant question is, could there actually be an option for happiness between Rune and Yamato after all? Rune is discovering unbidden desires within him—couldn’t Yamato too? If he doesn’t, how can he come to terms with “letting his friend down easy,” so to speak? Or must they sever their ties forever?

I make no claims as to what would have been the best or most tasteful answer to these questions, but I do know that none of them are solved by Ultimo’s most frequent answer to them: Yamato ignoring all questions and simply screaming, “AAAAAH!”

It’s supposed to be funny because it plays on Yamato’s confusion at, well, everything that’s going on. But in this context, it also comes across as his general gay panic.

I guess the narrative is careful to give him reason to panic by having Rune use Jealousy’s spiderweb powers the night before to trap Yamato in his bed so he can rape him. Which never happens, but very nearly does.

Would you like to know how Rune’s arc ends up? Well, after Rune’s already battled Yamato about three times and Jealousy’s already battled him about a thousand times, they fight again in postwar Japan (long story that I will get to) and Yamato finally admits that Rune wormed his way into his heart via a ridiculous speech that includes the phrase, “So I’ve decided to give. And giving…is for both boys and girls.” Maybe we can’t have Yamato say anything like “guess I’m bi after all” because the investors back at Jump HQ in Japan would rebel. Guess I’ll never know, but the result struck me as thoroughly uninspiring.

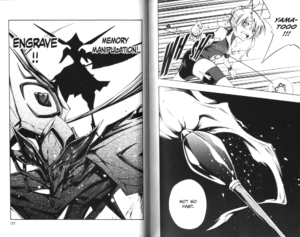

But then—guess what? Sayama, his original love interest, barges in, and she has the memory-manipulating dōji right now, so she wipes Rune’s memory clean. This moment doesn’t even get a dramatically satisfying tragic sequence of Rune in terror as he loses the one thing he truly desires—although even if it had, history still would not look kindly on Rune’s depiction for reasons I’ve already covered.

Then Sayama puts on a sly smile and asks, “Will you still love me, Yamato?” Without skipping a beat, Yamato grins and says, “Yes…of course!”

If you read this series and you invested any hope or emotional intensity into Rune, then…oh no.

Ultimo’s Last Act: Just Burn the Rest Off

I wanna feel bad for Hiroyuki Takei. Not to pull the rug out from under you readers, but Stan Lee did not actually write Ultimo from chapter to chapter. He’s credited with the original concept, and it’s quite easy to believe that he wrote the one-shot known as Chapter 0 (on account of how may captions there are and how bad it is), but this series is mainly Takei’s show.

And as I read through this manga a few weeks before this post, hurtling through with increasing impatience, I crafted a narrative in my head. At the time, Takei was juggling an outlandish amount of ongoing manga, including—at the very least—Shaman King Flowers, Ultimo, and a story about a suspiciously Ultimo-looking robot boy called Jumbor. That’s three lines, all waiting. On top of that, Ultimo was proving not to be the runaway success that the combination of three big names—Lee and Takei with the famous Jump magazine—had once seemed destined to make it.

The series was continually delayed. I imagine that whenever Takei did get back to it, he tried to simply go through the motions, writing out what remained as fast as possible without missing anything vital. And I can’t help but assume that he lost some of his passion under guilt. He didn’t make the manga’s twists as successful as he could and should have; he blew a weighty project with Stan Lee’s mug all over it; he had let the story fall by the wayside—of course I’m projecting here, but for me, it only makes sense to assume that Takei had all too many reasons to feel more and more dispirited by the project as time went on.

Now, though, the series is done. I can go back and appreciate all its best moments; I can feel some sliver of the hype it instilled in me; I can take in all that masterful art. And I can feel my eyes steadily glaze over, convinced that Takei was simply burning the rest of the plot points off in record time.

Vice…Back Again?

To summarize volumes 5 thru 8: the dōji run around and fight each other, trying to get evil ones to turn good or good ones to turn evil. Characters philosophize about their backstories while screaming their robot attacks, which is never any worse in execution than the typical shōnen manga but never reaches the heights Ultimo hit in the first four volumes. Worse—because it crushes the promise that this would be a game of changing hearts—nobody succeeds in turning a single allegiance one way or the other.

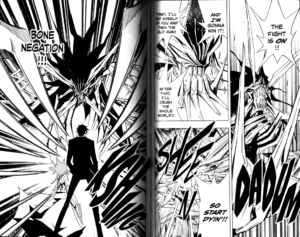

Instead, Vice attacks the good dōji for about the fifth time.

Now, in my view, having the biggest bad guy simply hang around and challenge good guys to battles now and then will almost inevitably kill that bad guy’s mystique, no matter how strong he is—especially when that bad guy is as talkative and mustache-twirlingly evil as Vice. We get what he’s all about from the word “go.” It’s not that I dislike him—like most mustache-twirlers, he can be funny and charming. But when he comes out of hiding to defeat yet another good dōji by, like, negating his bones, are we learning anything new about his personality? His powers? When you crush the heroes, you’ve proved your might—either prove your might again by doing something significantly different or you might as well stay home.

One of the more interesting things about Vice is that despite being the worst villain of all, his master is a total incompetent. In a fun twist, loser K could actually be his best possible master—but I’m getting off-track…wait…let’s stay on that track a little longer.

So I mentioned earlier that K is this story’s expression of the embodiment of truest evil: a nerd pervert NEET. The only totally new character Ultimo introduces in its second half is Jun, who, unlike K, is a depressed nerd pervert NEET. (Well, he’s never shown to be a pervert, but Takei usually draws him in nothing but his underwear, and I have a hunch that it’s being used as shorthand for “pervert,” but…don’t quote me on that.)

But maybe it’s not so bizarre that Ultimo’s brand of true human depravity is the loser shut-in…? I mean, I get what Takei was going for. For one thing, I imagine it would be very hard to make, say, a lobbyist for mass genocide and all forms of bigotry ever into a marketable villain in this comic made to appeal to young people.

For another, this is a manga that isn’t averse to meta commentary. In a move so horrible it’s actually clever, Eco tells one of his allies that to truly understand why Yamato has to be the leader of the good dōji, one has to read Jump…the very magazine that’s publishing Ultimo. (Well, technically Ultimo moved to Jump Square, but, semantics.) Therefore, if the ultimate good is a hero among otaku, then why not make the ultimate evil the “dark side” of the otaku world?

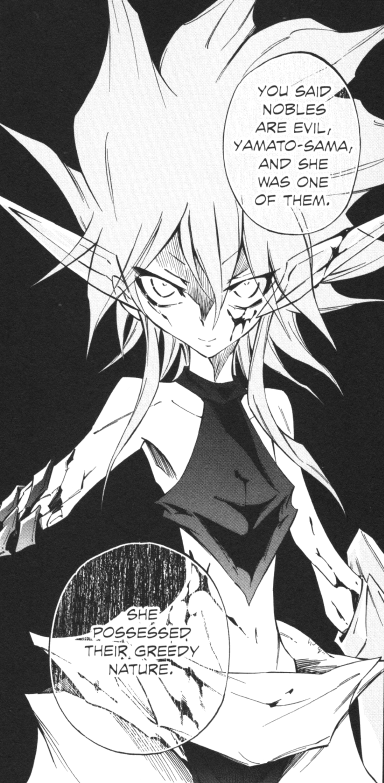

But as I was pondering this, I read what Rune has to say about why Jun is so evil and…squinted. Rune explains that Jun is a kid who only goes to high school twice a year due to bullying. When he retaliated with a utility knife, the school covered it up because his family was rich. Rune adds, “Humans who see others as mere numbers can no longer recognize humanity. The way I see it, they loosed a monster to save themselves.”

Did Rune skip something here? Jun hurt bullies in some unspecified way with a utility knife. This is seen as proof that he only sees all of humanity as numbers. The fact that his parents keep him in school is taken as proof that “they loosed a monster to save themselves.” There’s a chance that something is lost in translation, but my assumption is that the scene assumes that reader imaginations will fill in the gaps, helped by the dramatic grungy imagery around the utility knife and the ominous silhouettes.

In the end, Ultimo seems to proclaim that the truest evil—which Jun embodies no matter how many times others kick him around—is not caring about anybody’s lives, neither one’s own nor those of others. That sounds like depression to me, but in Ultimo it’s tied to what’s called, or translated as, “incompetence”: taking what belongs to others while providing nothing of your own. I bet that most people are going to read Jun as a dramatic, tragic, too-extreme-to-be-realistic figure with shades of Medaka Box’s Kumagawa. And yet, I’m just gonna say it, at the risk of missing the point, at the risk of sounding like everyone’s mom: Jun really just seems depressed and could probably use some counseling.

Back to the Past, and Then to the Future Again

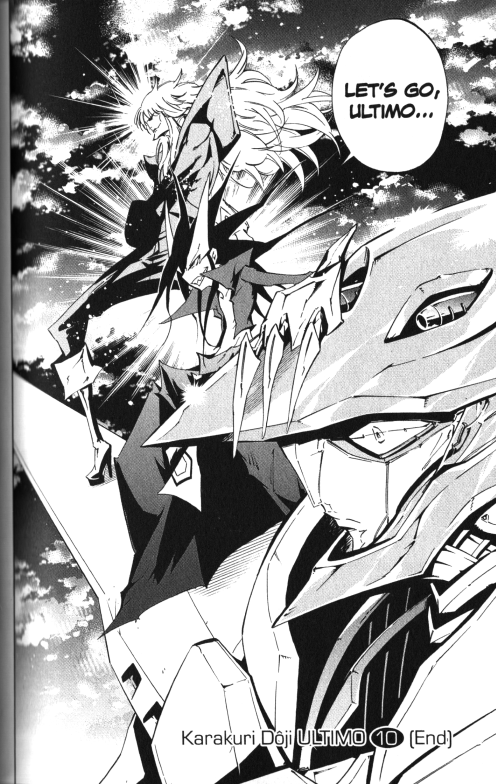

As I was saying, in volume 10, Vice beats up pretty much all the good dōji. Then he gets a powerup because now dōji can just get powerups by absorbing the abstract concepts of good and evil, so now his name is Vice Back from the Dark. Ultimo takes all the good people back in time, but since Vice can now steal powers (which is supposed to be the epitome of incompetence, but…doesn’t taking powers make you a competent thief?), he’s following Ultimo’s crew, unbeknownst to them (and gee, who could have predicted that).

In a thematic sense, it makes all the sense in the world to take this story back to postwar Tokyo, a city portrayed as a stark ruin with pockets of both depravity and goodness. Narratively, though, Ultimo bungles things yet again.

As cute as it is to learn about Ume’s past self by having the other characters meet her, and as much potential as her meeting with Yamato had for more deep character interaction—seeing as they were virtuous thieves in their past lives and classmates in the present—the story is so far gone at this point that it comes across as a dreary waste. Yamato and Ume have no time for an interesting interaction; after Yamato asks only his most dead-simple questions, we have to move on, see a splash page of the villains, and get amped for the next battle. Maybe that’s just the restrictions of shōnen manga at work—or, for that matter, any product that has to cater to the whims of an audience with certain action-focused expectations. It’s not a balance that later Ultimo strikes well.

The last twist in Ultimo that strikes me as simultaneously sensical and rife with opportunities for neat character interplay is the reveal of the dōjis’ true ultimate goal. It’s not a surprising twist, but there is something classic about it. For a while now, the dōji and their masters have begun to realize that rather than fighting each other in some strange game to determine whether good or evil is stronger, they should really be fighting their creator Dunstan, who not only messed up countless lives by dumping superpowered dolls into people’s hands, but also has godlike powers and unknown, no doubt insane motives. He is, after all, revealed to be a super-scientist who was so talented that the government allowed him to become immortal—which is the sort of ridiculousness I can get behind.

Why didn’t anyone in the 30th-century government predict that Dunstan, being over a thousand years old, might try something so dangerous and weird? We’ll never know.

And yes, this story does contain “Stan Lee fanservice” in the form of Dunstan walking around and occasionally becoming a dragon, but to my surprise, I never thought it went so overboard as to be grating, and I always liked seeing him show up. As a bonus, readers who hate Stan Lee might enjoy seeing the heroes constantly beat him up.

I say that now just to clarify what I didn’t get to mention before: the future is important to Ultimo’s timeline. It’s just not nearly as important as one would hope. The 30th century is used for exactly two things: the site of the dōjis’ creation, and the origin point of Murayama, who looks like an icy Proto Man of a rival at first but loses relevance as time goes on. There goes another promise.

Back in postwar Japan, what looks at first like a monster-of-the-week-style fight with one of the Seven Deadly Sins abruptly lurches into the final act. It starts when Yamato decides to recruit Hana and her dōji Eater to the side of good via battle. Merely deciding that in his mind somehow signals to Future Yamato that he must show Past Yamato (oh, sorry, they’re calling him “Hopeful Yamato” now) the future that this decision will create.

Thus, Yamato is whisked away to the future—where the final fight against Dunstan is happening (!…?). Not only that, but all the evil dōji are on Ultimo’s side (…??). Not only that, but Yamato finally learns something that will make his heart break: his true love Sayama is Dunstan’s daughter (…to be fair, this is a twist that readers were shown several volumes ago, and it was sort of cool at the time, but it didn’t lead to any of the kind of over-the-top nonsense I was hoping for, so my reaction is a definite “…”).

No sooner has Yamato been brought to the last few episodes of Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann than he’s spit back out into 1947. No sooner has that happened than more and more characters show up and battle, with less and less warning and reason. Rune and Jealousy ambush him and fight him for the final-final time, in a disappointing conclusion to Rune’s character arc with all the impact of a poked soufflé. Sayama shows up, barfs out a character arc about how being Dunstan’s daughter has made her lonely, and cries as Yamato and friends give her a stirring friendship speech. Other bad dōji show up and fight other good dōji. Then Dunstan shows up naked in a tree and declares that the Hundred-Machine Funeral has almost ended.

…Excuse me! Hasn’t it just started?

Yes, Dunstan’s here to inform us that the Funeral doesn’t take a year (nor does it start and end on that specific day in the 21st century which Yamato’s brief timeloop thwarted). It ends now! This is what I really meant when I said it feels like Takei is burning off the excess storyfuel as fast as possible: the timeline gets crunched for efficiency.

That storyfuel includes yet another moment with boundless potential. In the midst of some between-battle strategizing and recovery, Ultimo and Vice detach from the scrutiny of their masters to fight one-on-one—but end up confiding in each other.

Both admit that this game of good and evil, rather than sharpening their moral understanding, has only confused it. As they duel each other, they realize that the only way to be truly good is to thoroughly understand evil, and vice-versa. After this realization, Vice can no longer attain the strength he once could with pure selfishness alone. He’s gutted.

Ultimo and Vice don’t have a varied enough history of intriguing clashes to make this finale hit home for me. Plus, since the story has only had about 144 hours tops of narrative development time for its heroes, these two simply haven’t had enough onscreen time to, y’know, know good or evil. Also, the confrontation is brief, and feels even briefer and a tad more confusing thanks to the entrance of Jun and K. Nonetheless, it feels to me like this last clash was planned from the start.

With that, the most-truly-final battle can begin. All good and evil dōji congregate in the 30th century to confront Dunstan once and for all as Sayama attempts to stick her metaphorical knife in daddy Dunstan’s back. All the robots sync with their masters and combine to create their most perfectly ultimate selves. Dunstan makes copies of the dōji, and then he kills the copies. I don’t know what that was about any more than I understand the talk about Hopeful Yamato versus the other-timeline Yamatos, but don’t worry because that stuff’s all over now!

Sayama’s last plot-relevant moment ends up being disappointing in its own way. She may have given Dunstan some harsh words, but her abilities are of little use here. As Dunstan’s palace erupts, she falls, and now, with her aloof and high-minded exterior gone for good, she is a damsel in distress in Yamato’s arms. (That seems to happen often with Yamato: Ultimo, Rune, and Sayama have in the end become a series of babes in his arms.)

The ending is truly explosive, if by “explosive” I mean the art is pretty and there are tons of robots. Again, this is like the ending of Gurren Lagann, only with tiny character drama and foggy stakes. As the robots announce their respective final attacks, thematic celestial bodies, and so forth, Dunstan allows himself to be killed in their wake. But he announces his final creed: by killing him, the dōji and their masters have proved that what’s important is not being a paragon of good devoid of evil, but being a neutral person who strives to walk the path of goodness. In fact, he claims that now all the heroes and villains have become a new type of being who will lead the future of humanity down a brighter path.

…Wait, that’s not what he says at all. Why did I think he said all that?

Here are his exact words: “Unnngh!!! Mwa ha ha ha! Yes! That’s right, Mr. Yamato! The perfections’ noh powers make humanity possible…while the sins are like celestial objects ruling them! With all of them, humans reach their ultimate form! Thus…this form [Ideos Ultimo (it’s another powerup, don’t worry about it)] represents ultimate good and evil having overcome the ultimate challenge! This is the new humanity that I have sought across centuries for saving the world!!”

I just extrapolated a lot more meaning from those words than what was actually there, didn’t I?

With that, we return to the story’s present day. It’s a scene we’ve watched play out repeatedly, thanks to timeloop shenanigans: Rune bumps into Yamato, Yamato remarks that he’s very awake for this time of morning, and so on…

But things have changed. Ultimo’s gone! Wait, no he’s not, he’s right there. But he’s…a human! In fact, all of the dōji are now humans, and they’re living out everyday lives with their masters in a brief montage. Some people have changed a lot in the process of simply living, according to the narration, but the images suggest to me that none have changed since we last saw them. (In fact, Jun is still sitting alone in his room. Get that boy a friend!)

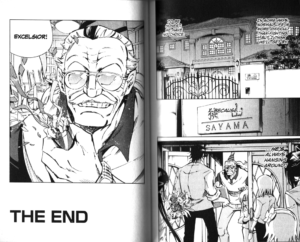

How is this supposed to lead humanity into a bright new era? Beats the heck out of me. But since Dunstan appears at the front door of a party in the last two pages and says “excelsior,” it’s supposed to be a perfectly happy ending. Sure, nobody died (and the dead one came back to life), but obviously that’s not the only qualification for a happy ending.

Remember This Mess

An opening with too much promise, squandered too soon. A rushed finale. Too many characters who felt like too few characters and got too little time to be anything but flat. Gorgeous art papering over a rickety construction site.

Ultimo was too big in my life for me to let it be forgotten. It’s never going to haunt me, and it won’t even lead me to ask any of the profound questions implied by its premise, but somehow it feels wrong to not mention it. I’m glad I did finish it. I’m glad I can think back on the good parts and scavenge mercilessly for elements that I can, perhaps, fold into my other fiction projects.

Ultimo is far from the worst shōnen story, and it may well be one of the most eye-popping. If you see all twelve volumes at the library, why not give it a try? It might get tedious, but hey, at least it’s not a hundred volumes of tediousness.

Most of all, thank you for reading, and Patrons, thank you for Patreonning.

And if you enjoyed this post but are NOT near a public library, why not read about me watching 4Kids TV or enjoying-not-enjoying BlazBlue?

…Excelsior???

Sounds like a bit of a mess, though I don’t follow any anime or manga personally. I can definitely sympathize with “oh crikey, I’ve been doing this creative thing for aeons now and I’ve got like eighteen plot threads running and I owe it to readers but I am SO OVER this world and story.”

I can too…it’s sad but true.