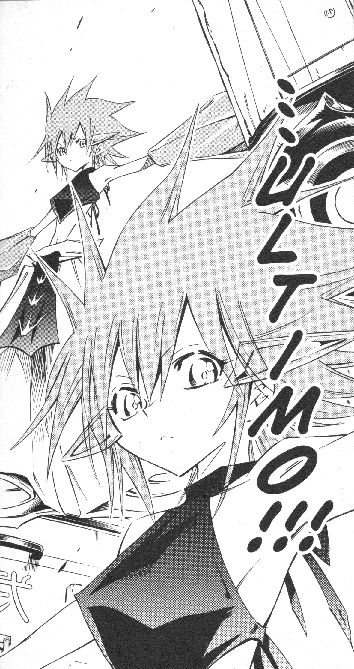

Recently I finished Ultimo, a manga which history will remember only as a footnote in Hiroyuki Takei’s career that weirdly has Stan Lee’s name on it. While I didn’t finish it back in the day (when, after many delays, it petered out into a ‘meh’ conclusion), I was always captivated by its high ambition, its sleek art style, and its sheer charm. Take Ultimo himself: his design strikes me as effortlessly cute, cool, and beautiful at the same time.

Cuteness and coolness. Beauty and strength. Today I notice that for Ultimo’s character, these are not contradictions. If anything, his beauty is implied to be the reason he embodies ultimate power and goodness.

And I wonder if anyone latched onto that. Did anyone furiously doodle Ultimo in the margins of school notes, not just because they thought he was kinda neat but because, deep down and perhaps subconsciously, they appreciated characters like him who weren’t just sidekicks, comic relief, or jokes?

If that question sounds overly specific, it’s because I’m pulling it from my meditations on characters I latched onto through my childhood and teenage years. It always seemed obvious to me that tomboys were the coolest characters in any kid’s show that included them. Manga characters occasionally me by surprise, not by revolutionizing my conception of what the supposed coolest character archetype was, but by emerging just off-center of that idea.

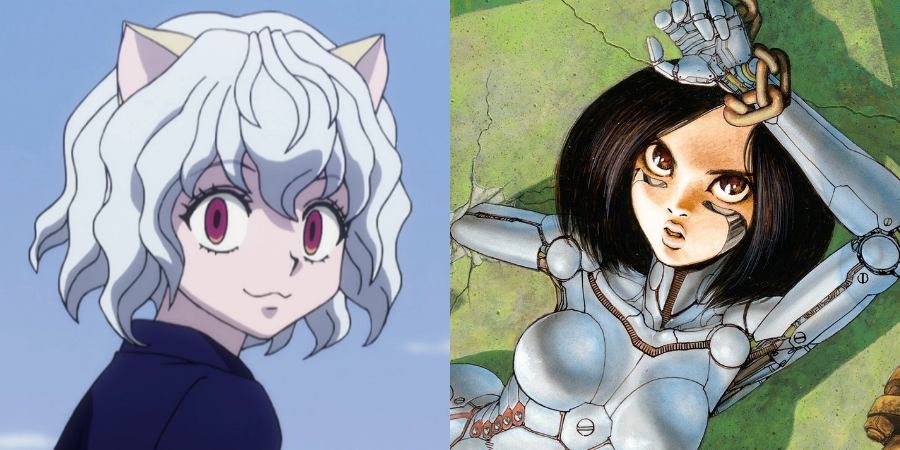

Neferpitou from Hunter x Hunter confused many readers by sporting a cute androgynous appearance while coming from an all-male species, but I didn’t think very hard about this and doodled him because he was simply cool and cute and a little edgy.

But the title character of Battle Angel Alita was a bigger shift. Beyond kicking people and doing actiony things, I can’t remember a time when she did anything tomboyish—at least, not in the rowdy cartoony sense. She was short, slender, and feminine—and rather than these things contradicting her strength, they merged with it, becoming what made her fighting style so effective. My body type was similar to Alita’s, and I hated being told not to lift things because I was a girl. (When people told me not to lift because of my scoliosis, it was, strangely, a different story.) While Alita wasn’t exactly a comfort character or an inspiration to me, I had respect and appreciation for her—very rare for me and fictional characters.

Since then, I’ve realized that my feelings about these characters are tied to me being agender. So I wonder if maybe, just maybe, someone out there doodled Ultimo in their class notebook because he merged or blurred gender roles in a way that struck them as…pretty cool.

People talk a lot about how they’ve connected magical girls to themes of LGBTQ+ empowerment, but in the world of 2010s-era shōnen manga, I’ve heard anecdotally that characters like One Piece’s Emporio Ivankov and Mr. 2 Bon Clay, and Naruto’s Orochimaru, struck a chord with many readers by bringing a type of cool that they’d never seen or acknowledged before. Mr. 2, Ivankov, and the rest of the Kamabakka Queendom are rare examples of shōnen sidekicks who, whether they’re crossdressers, drag queens, trans, genderfluid, or gladly refuse to be labelled, are amazing combatants who will not be reduced to brief gags. Orochimaru is no less of a serious threat for disguising as a woman or for having feminine or androgynous style. These characters are treated with their due respect in their universe; they’re not dismissed as weak contradictions.

But this is limited, right? For one thing, it’s not as if manga is a medium designed to give people in the Anglophone world positive representation for specific gender expressions or identities. It’s basically designed to make money, possibly worldwide but primarily in Japan—meaning, of course, that these manga are already being ported to a different context when I read them or read responses to them, and also meaning that for all the times I’ve indicated that Ultimo is transgressively cute and cool, I actually don’t know if that’s true in his original context. Further, the specific genre I’ve been focusing on—shōnen—targets boys and young men…and not the boys and men of some progressive future year, but of good ol’ 2010-ish. So we won’t see many Alitas as main characters. Nor will we get many overtly LGBTQ+ characters. And some bodies and aesthetics are valued more than others. An Alita is a more likely hero than a Mr. 2.

When I was in middle and high school, I didn’t think Ivankov or Mr. 2 were cool at all. I just thought they were as goofy as any One Piece character—and when your story’s main flavor of coolness is goofy coolness, that doesn’t necessarily increase the chances that the groups your story depicts will get any new respect in the real world. Meanwhile, I just thought Orochimaru looked like the disgraced Michael Jackson. Orochimaru is still a slimeball villain in the end, and readers can see him as cool for his gender expression about as easily as they can see him as even creepier for it. Personally, I latched onto nothing but the very specific identities that resonated with my own story. I had no curiosity about the others, and it’s taking me years and years to unlearn extremely bad habits—homophobia, transphobia, general ignorance, and more besides.

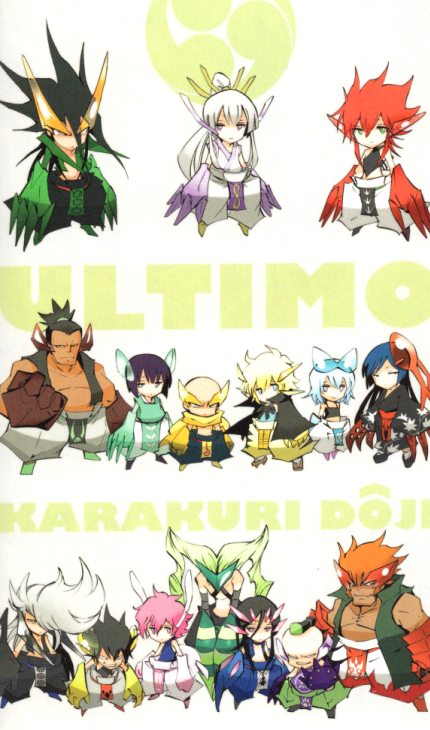

Back to Ultimo. The story centers around a cast of karakuri dōji, translated as “mechanical boys,” and while they are explicitly boys, they range from slight and feminine to huge bodybuilders whose age looks closer to twentysomething. All told, the dōji have about five styles: big buff man, feminine boy, masculine boy, cartoony masculine boy, and taller androgynous boy (yes, Paresse is the only dōji that goes in this category). It’s cool that the “girly boys” don’t get called out for anything like severe girliness. (I could say more about the discomfiting fact that Ultimo is portrayed as protagonist Yamato’s submissive sexual partner for comic relief…I’m not bothered by the gayness, I’m bothered by the pedophilic overtones…but that’s a talk for another article.)

It occurs to me now that maybe Ultimo’s feminine beauty is meant not to signal his transcendent goodness, but the uncanniness that is also part and parcel of his character—even his best friend Yamato can’t place his motives and is terrified when Ultimo’s conceptions of good go awry. So, like Orochimaru, that pretty strength can be read both ways: immaculate or disturbing.

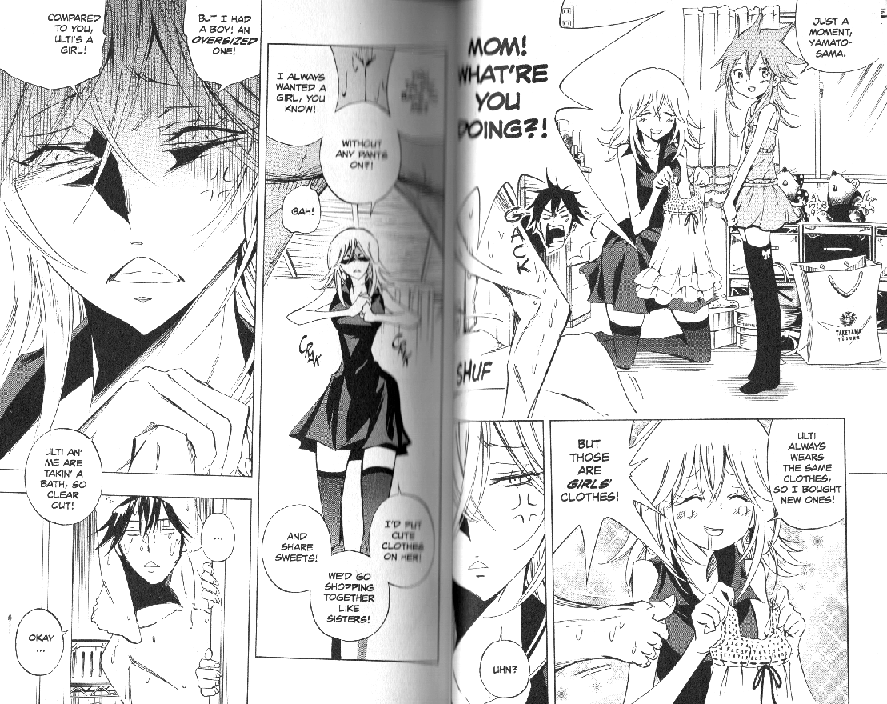

It’s quite a while before the manga enacts its first “Ultimo is super girly” joke. (It happens in volume 10…out of 12.) I want to drop in a word about this gag and gags like it, little things that readers are meant to chuckle at and forget. Click here to skip the casual “humorous” mention of domestic abuse, transphobia, and…okay, I can’t explain it without saying what it is, but if you have gender dysphoria, you’ll probably want to skip it. Also, mild blink-and-you’ll-miss-it nudity. Wow, this is sounding worse with every warning…

The scene begins with Yamato’s mom dressing Ultimo in girl’s clothes. Her dialogue on the second page reads, “You talkin’ back to me? Without any pants on?! I always wanted a girl, you know! I’d put cute clothes on her! We’d go shopping together like sisters! And share sweets! But I had a boy! An oversized one! Compared to you, Ulti’s a girl! Ulti an’ me are takin’ a bath, so clear out!” It’s punctuated with her pounding a fist into her palm.

Since this is meant to be a gag, the fact that she seems to be on the verge of beating her son is a deliberate exaggeration—of course she would never beat Yamato…and if she did, it wouldn’t go on for longer than a throwaway panel. No matter how serious the threat, the sentiment remains the same: she hates how Yamato can never be her idealized kind of girl. I have to imagine that many trans women would not enjoy reading this. Yet gags like this are not uncommon in shōnen manga.

To be clear, I don’t mean to indict the authors behind the gags. I mean to meditate on what people find or found funny, and why. I didn’t bat an eye at this gag when I first read it. (…Okay, yes I did, but that’s because I only finished Ultimo last week. It got really bad.) Why is a depressing subject like this turned into a joke? What happens when scores of people read it, respond to it, glance over it or, on rare occasion, feel some sting of trauma?

That being said, it is impossible for mangaka to safeguard their stories for every reader worldwide and their specific identity struggles. I’m thinking now of a moment in Battle Angel Alita: Last Order when Alita’s robot friend Sechs essentially brags, “Wow, my new male body is way stronger and better than your female one.” Arguably, the author did do some “safeguarding” when he kept Alita secure in herself, unconvinced by Sechs. That didn’t really matter to me, because the moment I read that as a teen was one of the few times in my life when I felt dysphoric.

I’m not going to suggest a change one way or the other because I know things will just change gradually with the tides of general social pressure, as these things tend to do—and it’s likely that they’re already changing. I just think it’s interesting and occasionally worthwhile to remember it, dwell on it, and move on.

Now, anyone who’s read much Ultimo knows that by focusing on a single gag more than anything else, I’m overlooking an entire overtly-LGBTQ+ character. That’s because there’s so much to talk about with that character (and there are so many spoilers) that I’m saving the subject for a later blog post about the entire series. So I have just enough material to mention casual moments like this. Or the time when Yamato learned that a tomboyish character was a reincarnation of a man, then remarked, “That explains it…” Or the time one character was warned, “You can’t do that. You’re a boy…” —okay, that’s getting close to spoilers again, I’ll discuss it later.

What do we find funny? Moving? Aesthetically pleasing? What figures, tropes, and bodies do we feel we’re allowed to consider “cool?” And who’s allowed to be a shōnen hero? I’m trying to learn more, expose myself more, and expand my notions of what gets to be tough, dark, pretty, special, prized and praised. Of what should be doodled on my notebooks…

Thank you for reading, and Patrons, thank you for Patreonning.

Check out my Ultimo full-series retrospective—because SOMEONE on the internet had to do it.

Or if you want something more LGBTQ+-related to wet your whistle (ignoring THAT ONE ULTIMO CHARACTER) (so badly handled it’s painful), check out this post about my personal experience of being agender.